The Qualitative Formative Assessment Toolkit: Document Learning with Mobile Technology

To assess your students’ ongoing awareness of what and how they’re learning, consider using cameras, screenshots, video, and screencasting as everyday classroom tools.

What is qualitative formative assessment? Some call it anecdotal or informal assessment. However, such designations imply passivity -- as if certain things were captured accidentally. I believe the word "formative" should always be included with the word assessment because all feedback mechanisms should help shape and improve the person (or situation) being assessed. Wedging the word "qualitative" into my terminology differentiates it from the analytic or survey-based measures that some associate with the term formative assessment.

For my purposes, qualitative formative assessment is the ongoing awareness, understanding, and support of learning that is difficult or impossible to quantify. An informal observation or the look on a learner's face can inform a teacher about a student's progress, yet such signals are challenging to capture or convey to the relevant agents (i.e., the learner, the teacher, or the parent).

Carly Schuler stated that the learner needs to be mobile, not the technology. Following that logic, the learner should be able to use technology wherever he or she is to document learning. Mobile technologies -- from smartphones to laptops -- possess four simple media-authoring approaches that make qualitative formative assessment more accessible and the processes of learning more audible and visible.

These approaches form the Qualitative Formative Assessment Toolkit (QFAT).

1. Making Photos

Cameras are powerful tools for capturing moments and documenting learning. You can take a picture of anything -- the room you are in or the weather outside. If each learner, every day, snapped a single image of something that he or she found interesting, a rich timeline of artifacts would result.

2. Taking Screenshots

Learners spend time using technology as part of their learning, but not all software or applications have a "save" button, especially in moments that may be more interesting than a final export. Enter the screenshot: a still image of whatever is happening on your screen.

Here is how to make one on various operating systems:

- iOS (Home + Sleep)

- Mac (Command + Shift + 3)

- Chromebook (Control + Window Switcher)

- Android (Volume Down + Power for 2 seconds)

- Windows (PrntScren and then Ctrl + V)

Imagine a photograph of a classroom and then a screenshot of an app being used. When juxtaposed, the experience with the app becomes situated in a temporal and/or spatial context, forming a powerful reflective agent.

3. Filming Videos

Video adds movement and sound to the documentation of learning. Think of an experiment that is underway or a panorama of a classroom busy at work. Filming each captures moments of time, space, and experience that drive inquiry:

- Why did the learner choose to film this moment?

- What was happening?

- What do these choices tell me about the learner?

A Quick Hands-On Break

Let's practice.

- Make a photo of the room you are in.

- Open this blog post and take a screenshot of your browser.

- Film a short video of a watch, clock, or calendar.

You now have three artifacts on your device from a single experience. They are saved on your photo roll, gallery, or desktop.

4. Screencasting

Screencasting is the process of recording what is happening on a device screen with audio narration to make a video file. In the past, this process was complicated or expensive. With the emergence of both built-in operating system tools and well-designed third-party applications, screencasting has become more accessible.

You simply need a tool that lets you arrange the previously collected artifacts (photos, screenshots, and videos), string them together in some sort of timeline or layout, and add a voiceover.

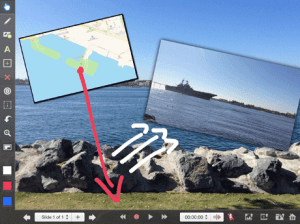

iMovie for iOS or Mac OS X can do this. So can Windows Movie Maker. With a tool like Explain Everything, you can include annotations and animations such as text titles, object movements, drawings, and callouts -- all increasing the ways for a learner to describe or express learning and understanding.

A screencast does not need to be long. Imagine if every student made a 60-second artifact of learning every few days. Today, this is not difficult to achieve.

Keys to Making It Work

Here are some key ideas from my research that inform the QFAT:

Gradually release control of and responsibility for learning to students.

The authoritative agent (usually a teacher) needs to be OK with not always knowing the direction students will take and that each student's representation of understanding will be different.

Let go of polish and "final" drafts.

Shift away from final products and toward cumulative and cyclical iterations of learning. The process is the product.

Have a system for artifacts.

A book. A website. A file repository (like Dropbox or Google Drive). Use whatever already works for you. . . or find a new system that works better.

Find intrinsic value in the process.

The authoritative agent has to recognize and value the process afforded by the QFAT. For someone with a much different definition of teaching, learning, and assessment, this way of thinking will feel like "more work."

Provide access to any number and type of mobile technologies.

While a 1:1 (standard device or BYOD) would certainly make this process accessible, it could also be achieved with a single smartphone.

One does not need to use all four components of the QFAT every time learning is documented. In isolation, each artifact is powerful. When you bring them together in a deliberate and thoughtful way, though, something that was not possible without the technology becomes easily accessible and immediately useful.