How Instructional Coaches Can Use Co-Teaching to Support Teachers

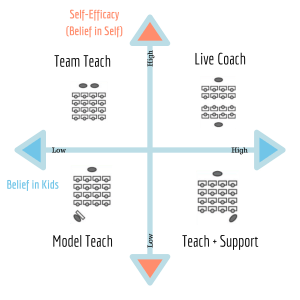

A matrix based on a teacher’s belief in themselves and their belief in students can facilitate effective instructional coaching.

Hannah Thompson was in her first year of teaching, and like many novice teachers, she lacked confidence in her ability to do the job. (I changed the names in this article to protect confidentiality.) Her class management skills were still undeveloped, and her fourth-grade students required more structure and consistency.

Not knowing that many first-year teachers face similar challenges, Ms. Thompson was on the verge of quitting. She needed a full-scale intervention, and as an instructional coach, I was called in to help.

Benefits of Intervening in the Classroom

Co-teaching can be effective at accelerating teacher skill-building. Ms. Thompson needed someone to reinforce the idea that her students were capable of meeting expectations, and she needed to feel that she was capable of leading the class. I assessed that she had a low belief in herself but did believe that her students were capable of meeting expectations because she saw how they engaged in their special classes and in the cafeteria.

Over the next three days, I spent many hours in the classroom, pulling students out as necessary, circulating around the classroom, and occasionally addressing the class. Ms. Thompson started to repeat my behaviors. At the end of the third day, we debriefed. “I didn’t think it was possible for me to get through a whole math lesson like this!” she said.

“And you did it because you narrated behavior, held students accountable, had clear directions, and much more. You have learned so many skills in such a short amount of time,” I replied.

As this example illustrates, intervening in the classroom can do the following:

- Reinforce positive mindsets about student(s): “I didn’t know that my kids could do that!”

- Reinforce positive beliefs that teachers hold about themselves: “I didn’t think it was possible for me to…”

- Make explicit connections between teacher actions and student actions

- Build a lot of teacher skill

Risks of Intervening in the Classroom

But there are some risks if leaders do not assess the situation correctly. For example, Ryan Dawson was a middle school math teacher who also had classroom management difficulties. I thought modeling would be the best course of action. I planned the lesson and was ready to go. Almost immediately, students started yelling at me, “Are you here because our teacher sucks?” Mr. Dawson looked on in horror as students started moving out of their assigned seats, putting on their headphones, and talking to each other. While I was able to regain some control, it was ultimately a bust.

After the lesson, Mr. Dawson said, “See! What did I tell you?” The modeled lesson had reinforced negative mindsets about his students, and he used that as an excuse in every future conversation.

Unfortunately, I had not assessed the situation correctly. In prior conversations, he had blamed the kids for every problem he was having. He had high belief in himself and low belief in students. Modeling was not the way to go. Mr. Dawson continued to believe that it was the students’ fault, made little effort to improve his performance, and was released from his contract at the end of the school year.

Decision-Making Matrix

After years of testing, iterating, and refining, my team and I finally figured out the two factors that influence how to intervene when a teacher needs support. First is the extent to which the teacher believes in their students, both academically and behaviorally. The second factor is whether the teacher believes in themselves and has high or low self-efficacy.

Coaches and administrators can use the following matrix to determine their action.

Team Teach: If the teacher has high self-efficacy and low belief in their students, a coach would choose to team teach. Teacher and coach teach the class together after planning a clear delineation of responsibility. For example, the coach may choose to open the lesson and turn it over to the teacher for guided practice. Having additional capacity in the classroom can demonstrate to the teacher that the students are capable of meeting expectations and learning outcomes with the right guidance and support.

Live Coach: If the teacher has high self-efficacy and high belief in students, a coach should live coach. In live coaching, the teacher teaches the class. The coach offers live guidance to the teacher and does not address the class. This may look like using hand signals in the back, offering quick feedback to the teacher when students are working on another task, or even acting like a student (e.g., “Ms. Thompson, can you help me figure out what page I am on?”).

Model Teach: A coach should model if the teacher has low belief in self and students. The coach teaches the class while the teacher observes. They observe a number of teacher moves and can see how the students react to each of them. In the debrief, the coach speaks to each move, decision, and result. Video-recording the lesson is also good practice.

Teach and Support: Like Hannah Thompson, if a teacher has low belief in self and high belief in students, the teacher teaches the class. The coach addresses some students directly or occasionally addresses the whole class. I knew Ms. Thompson needed a win because she felt defeated in her progress as a teacher. She had a lot of technical classroom management skills to learn at once, and so the model we chose allowed us to reset student behaviors and reestablish key procedures.

Sometimes our classrooms devolve into places where learning is hard, and an instructional coach or administrator can help to put it back on track. The decision to adopt different coaching strategies has some risks but can also have tremendous rewards. Weeks after the intervention with Ms. Thompson, I came back to see her in action again. She had maintained the changes, and her classroom was now a place of learning.