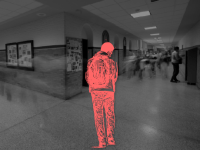

Hard Steps Not Yet Taken: Ending Bullying in Our Schools

While we have made progress in reducing bullying and related behaviors in many of our schools, the problem persists in too many others. This is partly because we see it as an "engineering" problem, when in fact it is more of a philosophical and moral one.

Since there is abundant guidance about what to do to end bullying, I wanted to get a different perspective from the voice of an advocate. Dr. Stuart Green is the director of New Jersey Coalition for Bullying Awareness and Prevention. Dr. Green has fielded numerous calls for over a decade from parents about children who have been bullied with slow or inadequate responses from their schools. This has been true even in states like New Jersey with strong, clear anti-bullying laws.

I asked Dr. Green to speak about the hard steps schools have not yet taken, but must take, to eliminate even the occasional ignoring or tacit support of bullying in schools.

Edutopia: Are there commonly used strategies that are ineffective, or downright harmful?

Dr. Stuart Green: Definitely. Children should not be advised to be "less sensitive," or to work harder to make friends, especially with those who hurt them. Bringing targeted children together is problematic, stigmatizing. It's one thing if children in similar situations seek each other out for support. It's another thing if schools gather targeted children together to provide counseling, for example.

Schools sometimes bring together children bullied and those who hurt them in order to work out their difficulties. That's essentially treating a mugging or a partner violence situation as if it was a communication problem. It also inevitably implies that both children bear equal responsibility for the aggressive act -- not true in the case of bullying -- or mugging! Even if the children involved (the child hurt, the child harming) seem equal (in social or physical power), if one child is more consistently aggressive, the relationship is unequal.

Further, having children discuss their victimization experience in front of the aggressor inevitably re-traumatizes the victim and empowers the aggressor.

What other kinds of things do schools do that don't really help?

It does not help to ask children (or parents) to write a report about a bullying incident. Hurt children commonly experience it as stressful and negative; it conveys being involved in a legal -- as opposed to educational and supportive -- environment. Bullied children or families asked to write statements also feel as if they -- rather than the school -- are making the case or bringing accusations.

What is your view of counseling for victimized children?

Counseling the bullied child is not enough. Once a child is targeted, having access to counselors is not sufficient. Adult mentorship is critical. A specific staff member should be designated to engage with a child, become aware of the child's situation, preferences, and needs. They should then actively work to increase the child's constructive involvement with the school. But this should be happening for all children.

When counseling (as a form of staff support) is offered only to the targeted child and only after the child is harmed, it conveys to the child and family that the school feels the child needs to change, and even that the child has been responsible in some way for having been harmed.

If counseling must occur, it should be made clear to the child and family that the counseling is supportive because what the child has experienced is traumatic, not because the school feels the child needs to change. Ideally, such counseling should not be known to other children and it is best for it to occur outside the school.

Are schools sometimes naïve about how to treat children who bully, maybe thinking that with a little bit of corrective action, he or she will "learn their lesson"?

Schools must promptly help children who bully. Children not helped to become less aggressive during school years are at significant risk for future life problems, including a higher likelihood of anti-social behavior and legal problems as adults. Children who both bully and are bullied repeatedly (referred to as 'bully-victims") are at most risk and need additional attention.

Sometimes children who hurt other children are popular with adults and have high social status in school. It can be difficult for teachers, as well as parents, to believe that (otherwise) high-performing and/or popular children can hurt peers, so confronting the issue is delayed. This is like not treating an infection that is contagious. It endangers the individual and allows the potential for harm to more people.

What is the biggest mistake you see schools make?

Over-focusing on incidents, not looking for patterns. While the law allows for single incidents to meet the definition of HIB (harassment, intimidation, and bullying), bullying, in reality, occurs repeatedly. In 15 years of taking calls from parents, I've never received one call in which a parent said their child was bullied once, never before and never after. Too often, a child is harmed for months, or even years, before schools take adequate action.

When an incident is noticed or reported, the school must assume a pattern may exist, and actively look for it. If bias is a factor (the child harmed has actual or perceived minority status of some kind), the school should consider there might be a gap in school culture, so that such minorities are made especially vulnerable in this school at this time.

In Summary

There is just no reason for schools to accept any form of bullying behavior. It is not a developmental norm, being a victim does not toughen up anybody, and letting students who bully "slide" only sets the stage for more serious and dangerous problems later on.

Schools must make hard, prompt, and professional decisions that will create a healthy, productive, and safe learning environment for everyone, regardless of ability or other personal characteristics. As my colleague, Larry Leverett, has taught me: no alibis, no excuses, and no exceptions.