Growth Mindset and the Common Core Math Standards

For many years, intelligence was thought to be static (fixed) and could not be altered. Informal research has shown this to be particularly true when it comes to students thinking about their mathematics intelligence. But with the advent of advanced technology and cognitive labs, psychologists and neuroscientists have found that aspects of intelligence -- and even intelligence itself -- can be altered through training and experiences.

Exposing individuals to new learning experiences serves as a way of working or exercising the brain. As we know that we can strengthen a muscle, system or reflex through exercise, it makes sense that exercising the brain would make it stronger. The brain becomes stronger when we learn something unfamiliar, creating new connections that can be stored in memory and providing frameworks to link new knowledge by association. In other words, as Anita Woolfolk writes in Educational Psychology, "What we already know determines to a great extent what we will pay attention to, perceive, learn, remember and forget."

Fixed Mindset vs. Growth Mindset

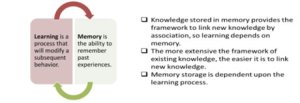

Brain scientists define learning as a process that will modify a subsequent behavior, and memory as the record left by a learning process. However, learning and memory are dependent on each other, as illustrated below.

But we hope to go beyond just providing a new learning experience. Carol Dweck, in her work at Stanford University, bridges developmental psychology and social psychology to examine the self-conceptions (or mindsets) that we use to structure the self and guide behavior. In her research regarding student motivation, she has studied the origins of mindsets, their role in motivation and self-regulation, and their impact on achievement and interpersonal processes.

Dweck's book Mindset includes research with 373 seventh grade students with equal prior math achievement to determine how a fixed mindset (the belief that intellectual abilities are fixed) compared to a growth mindset (the belief that intelligence can be developed) impacted math achievement. In her eight-week intervention program, some of the students were taught study skills and growth mindset -- or how they could learn to be smart because the brain is a muscle that becomes stronger with use. The control group learned the study skills but not the growth mindset (or expandable theory of intelligence). The results of the study showed that the treatment group -- the students who embraced the belief that intellectual abilities can be cultivated and developed through application and instruction -- had marked improvement in grades and study habits compared to the control group. By the end of the fall term, the math grades had jumped apart and continued to diverge over the next two years.

Praise and Perception

Additionally, in a 1998 study at Columbia University with Claudia Mueller, Dweck investigated the relevance of the types of praise that teachers offer students in conveying mindset. This study, conducted with fifth grade students, shows that when teachers use personal praise (for their intelligence), it tends to put students in a fixed mindset, whereas using process praise (for their effort or procedure) tends to foster a growth mindset.

Dweck’s mindset theory goes hand in hand with the Common Core's Standards for Mathematical Practice (SMPs) in conveying a growth mindset in the classroom. The key difference between fixed mindset and growth mindset teachers is in how they view struggling students. The fixed mindset teacher perceives these students as not sufficiently bright, talented or smart in the subject, whereas the growth mindset teacher sees struggling students as a challenge -- as learners who need guidance and feedback on how to improve. Growth mindset teachers see the challenge as an opportunity for students to learn when their efforts and mistakes are highly valued.

First and foremost, the SMPs stress the relevance and importance of persevering in solving a problem and learning from mistakes, which echoes the growth mindset of valuing and learning from mistakes. Additionally, the SMPs focus on using multiple processes and procedures for solving problems, and on students being able to share their various ways of solving problems. As Dweck found, process praise for effort or procedure was powerful in developing growth mindset, so it's important for students to have opportunities to learn and use different processes and procedures in solving problems, and for teachers to praise the process and not the person.

Expanding Math Intelligence

Ultimately, the SMPs provide ample opportunities for making connections and exercising the brain. In offering a variety of instructional strategies and activities, growth mindset teachers maximize opportunities for multiple interactions with mathematics. A classroom steeped in the SMPs allows students to actively discover, interpret, analyze, process, practice and communicate -- all of which have the potential to move information from working memory into long-term memory, ultimately expanding brainpower and mathematics intelligence.

Growth mindset, the belief that intellectual abilities can be cultivated and developed through application and instruction, and the SMPs are all integral parts toward helping students become successful in math. But more importantly, these three elements are critical in helping students become life-long learners and problem solvers.