When Students Are Traumatized, Teachers Are Too

Trauma in students’ lives takes an emotional and physical toll on teachers as well. Experts weigh in on the best ways to cope.

Alysia Ferguson Garcia remembers the day two years ago that ended in her making a call to Child Protective Services. One of her students walked into drama class with what Garcia thought of as a “bad attitude” and refused to participate in a script reading.

“I don’t care if you’ve had a bad day,” Garcia remembers saying in frustration. “You still have to do some work.”

In the middle of class, the student offered an explanation for her behavior: Her mom’s boyfriend had been sexually abusing her. After the shock passed, the incident provided an opportunity for the class—and Garcia—to provide the student with comfort, and to cry.

When Garcia first started teaching, she wasn’t expecting the stories her students would share of physical and sexual abuse, hunger, violence, and suicide. The stories seemed to haunt her all the way home, she says, recalling nightmares and sleepless nights spent worrying about her students. They also dredged up deep-seated memories of her own experiences with abuse.

“When you’re learning to be a teacher, you think it’s just about lesson plans, curriculum, and seating charts,” said Garcia. “I was blindsided by the emotional aspect of teaching—I didn’t know how to handle it. I was hurt by my students’ pain, and it was hard for me to leave that behind when I went home.”

The Real Costs of Trauma

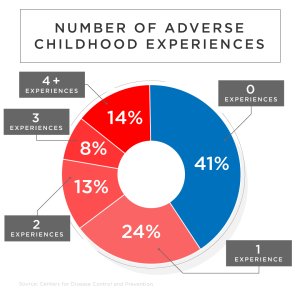

Data shows that more than half of all U.S. children have experienced some kind of trauma in the form of abuse, neglect, violence, or challenging household circumstances—and 35 percent of children have experienced more than one type of traumatic event, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can have impacts that extend far beyond childhood, including higher risks for alcoholism, liver disease, suicide, and other health problems later in life.

Trauma in children often manifests outwardly, affecting kids’ relationships and interactions. In schools, the signs of trauma may be seen in a student acting out in class, or they could be more subtle—like failure to make eye contact or repeatedly tapping a foot. (To learn more about how trauma impacts students, read “Brains in Pain Cannot Learn!”)

For teachers, who are directly exposed to a large number of young people with trauma in their work, a secondary type of trauma, known as vicarious trauma, is a big risk. Sometimes called the “cost of caring,” vicarious trauma can result from “hearing [people’s] trauma stories and becom[ing] witnesses to the pain, fear, and terror that trauma survivors have endured,” according to the American Counseling Association.

“Being a teacher is a stressful enough job, but teachers are now responsible for a lot more things than just providing education,” says LeAnn Keck, a manager at Trauma Smart, an organization that partners with schools and early childhood programs to help children and the adults in their lives navigate trauma. “It seems like teachers have in some ways become case workers. They get to know about their students’ lives and the needs of their families, and with that can come secondary trauma.”

When you’re learning to be a teacher, you think it’s just about lesson plans, curriculum, and seating charts. I was blindsided by the emotional aspect of teaching—I didn’t know how to handle it.

Vicarious trauma affects teachers’ brains in much the same way that it affects their students’: The brain emits a fear response, releasing excessive cortisol and adrenaline that can increase heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration, and release a flood of emotions. This biological response can manifest in mental and physical symptoms such as anger and headaches, or workplace behaviors like missing meetings, lateness, or avoiding certain students, say experts.

Yet many teachers are never explicitly taught how to help students who have experienced trauma, let alone address the toll it takes on their own health and personal lives. We reached out to trauma-informed experts and educators around the country to get their recommendations for in-the-moment coping strategies and preventative measures to help teachers process vicarious trauma. We share their tips below.

Talking it Out

Garcia, now a teacher of eight years, says she’s found that confiding in others—either a therapist, her boyfriend, or colleagues—helps her process students’ trauma and her own emotions.

Connecting with colleagues to talk through and process experiences can be invaluable for teachers coping with secondary trauma, according to Micere Keels, an associate professor at the University of Chicago and founder of the TREP Project, a trauma-informed curriculum for urban teachers.

“Reducing professional isolation is critical,” said Keels. “It allows educators to see that others are struggling with the same issues, prevents the feeling that one’s struggles are due to incompetence, and makes one aware of alternative strategies for working with students exhibiting challenging behavior.”

It doesn’t serve anybody to pretend that we’re teacher-bots with no emotions, which I think sometimes teachers feel like they have to be.

Finding a wellness-accountability buddy—a peer who agrees to support and keep you accountable to your wellness goals—or using a professional learning community as a space to check in with other teachers are also ways to get that support, offers Alex Shevrin, a former school leader and teacher at Centerpoint School, a trauma-informed high school in Vermont that institutes school-wide practices aimed at addressing students’ underlying emotional needs.

At Centerpoint, time for a monthly wellness group—where teachers, administrators, and social workers support each other on their personal wellness goals like exercising and creating work-life balance—is built into the professional development schedule. Staff also use in-service time to focus on taking care of their health together, by hiking, biking, going to the gym, or even learning to knit.

“If I had one wish for every school in the country, it would be that they made time for teachers to really sit down and talk about how they’re feeling in the work,” said Shevrin. “It doesn’t serve anybody to pretend that we’re teacher-bots with no emotions, which I think sometimes teachers feel like they have to be.”

Building Coping Strategies

Students affected by trauma can have combative personalities and learn which buttons to press to upset you in class, says Garcia. When a student acts out in class, Garcia takes a few deep breaths, drinks coffee, or goes to a different part of the classroom to help another student.

“If I get upset, it never goes anywhere,” Garcia said. “When you try to have a battle in class, you automatically lose as the teacher.”

That’s a good approach, says Keck, who suggests developing proactive coping strategies to address stressful situations in advance. A strategy may be counting to five, visualizing a calming place, or responding with an opposite action—like talking to a student quietly when you want to yell. Waiting until you’re actually in a stressful situation means you’re likely to overreact or to say or do something unhelpful.

Keck also recommends mapping out your school day and taking note of the times of day you feel most stressed, and then integrating scheduled coping strategies into your daily routine. If you feel stressed when students start to lose focus midday, for example, guide your students in a quick group stretch and some deep breathing to shift energy before getting back to work.

“Look at your schedule. If you see a stressful pattern, don’t wait for it to happen. Don’t wait to feel overwhelmed and stressed,” urges Keck.

The important part is customizing the strategy to meet your needs.

Garcia applies this strategy when she’s at home. She knows that after she puts her daughter to sleep, the worry for her students creeps in—so she makes sure to take time for things she enjoys, like watching movies and playing video games.

While many teachers say they don’t have time for self-care, experts insist that it’s necessary to develop long-term self-care practices—and stick to them—to build up your overall well-being and resilience. These self-care activities could be going for a walk, reading, watching a movie, practicing mindfulness, or talking with a friend—whatever invigorates you.

Establishing Coming Home Rituals

It can be hard to leave work at work, but to address vicarious trauma, teachers need to create clear boundaries between work and home life. Part of that can be developing a ritual or routine that signifies the end of a work day, either before you head home, on the way home, or at home.

“For me, sometimes it’s just as simple as turning off my work phone before I go into my house,” Shevrin says. “I hear the sound of my phone turning off and then I know that I’m home."

After an emotionally difficult day, many teachers will write about their experiences before they leave, or sit down with a colleague to help process it, Keck told us.

Others organize their desk or create a to-do list for the next workday so they can let go of worry before heading home. While driving home, teachers listen to audiobooks, call a friend, or sit in silence to decompress. A ritual could even be as simple as changing clothes or taking a bath once you get home.

For Garcia, it’s about putting her daughter’s needs first and making the most of the time she has with her.

“It’s very easy to get overwhelmed and let the job consume you. But teaching is about balance,” she said. “When I come home, I try to just focus on my kid so she gets as much of me as she can. It’s not always easy, but I’ve learned to put my life and my daughter’s life first.”