Rural Students Reap Academic Gains from Community Service

In Fowler, California, one school district weaves farm-focused service learning throughout the curriculum.

From the communities of Fowler and nearby Malaga, in California's Central Valley, vineyards stretch out to the horizon, the rows of grapevines interrupted only by an occasional cluster of farmworkers. In packing plants dotting the outskirts of town, wooden and plastic raisin crates are stacked high.

In these communities of some 7,000 people altogether, descendants of Dust Bowl refugees live near grandchildren of Japanese-American internment camp survivors, a taqueria is housed in the Punjabi-owned market, and children of farmers, farmworkers, doctors, and packing-house employees sit side by side in school.

These children also garden together. And help immigrant adults pass their citizenship tests. And provide meals for local homeless folks. They collect sunscreen and lip balm for local farmworkers, and they pack up shoes, socks, and toys for kids in Mexico.

With a districtwide focus on community-service learning in classrooms, after-school clubs, and individual projects, the Fowler Unified School District's small student body -- 2,300 students in six schools -- makes a big impact. Its students have racked up tens of thousands of service hours in the past few years. And in light of the students' excellent rates for attendance and graduation and their rising test scores, school leaders believe that service learning engages students and enhances academic success at every grade level.

Everyone Plays a Part

The Fowler school district embraces traditional community service (in which individual students, classes, and clubs provide service to others) as well as service learning. The latter is a teaching strategy in which classroom academic content and service projects are woven together to simultaneously encourage students' academic and civic development.

Service-learning advocates believe that students learn more, and more purposefully, by applying their classroom knowledge to help their communities. In Fowler, that means learning by completing projects on school campuses and in the area.

This focus developed organically, according to Superintendent John Cruz. In the mid-1990s, Fowler parents requested that schools emphasize character education, teaching students in ways that have a positive impact on their values.

In meetings with families and community members, the district developed the Big Ten -- character traits like work ethics and trustworthiness -- to be taught and practiced in every classroom through the regular curriculum. "After three or four years," Cruz says, "we thought that it's nice to teach this in the classroom, but we have to take it outside to the greater community."

After doing some research, teachers on the districtwide Character Education/Service Learning Committee became convinced that such service could engage hard-to-reach students as well as the general student body. They began advocating for service projects at their schools, and the district brought in the Fresno County Office of Education for service-learning training.

Now ten years into it, every student -- regardless of grade level -- in the entire district is expected to get involved in service at school. Depending on teacher interest and experience, projects range from two weeks to a full semester.

The district's middle school and high school have an annual service requirement. At Fowler High School, students in grades 9-12 develop their own community-service projects, and their service hours are logged onto transcripts that can lead to special commendation at graduation.

Service That Makes a Difference

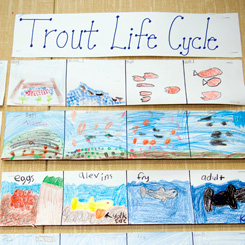

Projects in the Fowler district are anchored in providing genuine service. Under the direction of teacher LeAnn Hodges, for instance, third graders at John C. Fremont Elementary School addressed the nearby San Joaquin River's decline in trout population due to degradation of habitat.

In an extended service-learning project called Trout Go to School, students raised trout in their classroom. With a donation of 30 fertilized trout eggs from the California Department of Fish and Game and a 20-gallon tank and a water-cooling device provided by the Fresno Fly Fishers for Conservation, students monitored water temperature, fed the newly hatched fry, and released the tiny trout into the San Joaquin.

Sam Davidson, California field director of the national advocacy group Trout Unlimited, says of the school's efforts to protect trout habitat in California, "There is wide acknowledgment that without involvement in these efforts by young people, we will ultimately fail or fall short of the results needed to sustain our state's remarkable fish heritage."

At nearby Marshall Elementary School, set on the edge of a vineyard, even younger students learn firsthand about farming and ecosystems. First and second graders from the Marshall Garden Club grow strawberries, tomatoes, peppers, and herbs, delving into basic plant science and connecting their experience to the classroom curriculum. But this isn't just a fun science-education project: Their garden creates an outdoor learning lab for the whole school, according to teacher and garden-club coordinator Suzie Dondlinger.

When her colleagues teach about life cycles, she says, "they can bring their classes out and see ladybugs and praying mantises, and they can teach about natural predation." One pint-size gardener, a second grader named Trevor, sees an even bigger impact: "By planting plants, we make the environment better. The plants create oxygen, and because of the air being polluted so bad here in the valley, it helps the planet a lot."

Engaging Students and Standards

Educators in Fowler find that not only do these projects get kids interested in learning but they're also, says Hodges, "a great way to teach the standards without having to rely exclusively on book, pencil, and paper lessons." The trout project addressed third-grade state-mandated standards in content areas like science, math, and language arts. Students drew stages of the trout life cycle, used a formula to calculate when the eggs would hatch, created timelines, and wrote about the experience.

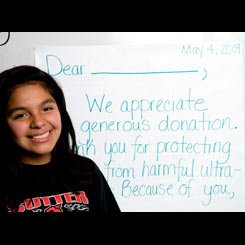

At Sutter Middle School, teacher Monica Sigala's language arts students were learning to perfect the art of letter writing while simultaneously reading about the contributions of farmworker advocate (and local hero) César Chávez. And in science class, these same kids researched the effects of ultraviolet rays. Their seemingly unrelated studies led students to pull together a service-learning project -- the Chávez Caring Crew -- in which they collected sunscreen and lip balm to help protect field workers from overexposure to the sun.

Sigala's student groups synthesized information about the Sun's effects, wrote letters to local businesses requesting donations, and created information cards in English and Spanish to accompany their collected items. Students take complete ownership of their learning, says Sigala.

"They're walking around saying, 'That was my idea. I came up with the sunscreen.' Or, 'I thought of sunglasses, because I found research that showed that ultraviolet rays can increase the risk of cataracts,'" she says. "The students don't even realize all the great stuff they're learning, because they're so involved with the project -- and all of this teaches the standards."

Service learning also engages the most at-risk students in the Fowler schools. High-school-level students come to Casa Blanca Alternative Education School because they've struggled academically in other settings. Once at Casa Blanca, they use math and a variety of other skills to do construction projects that benefit the district and the town, like the shed, the teacher-demonstration table, and the perfectly scaled-down student benches in the garden at Marshall Elementary School.

James (not his real name), a student who received many Fs his freshman year and who was a chronic truant until he moved to the Fowler district, surveys his shed with pride. "We accomplished something for the little kids," he says. James, who is graduating from Casa Blanca, attributes much of his success to service learning. "Every day, this is what I love coming to school for -- doing projects and building stuff for the community," he explains.

James also points out that it's more critical to do work right the first time on a construction project than on a math worksheet, where he can easily rework mistakes. "If you mess up on the real project, you can't just erase it. You've got to buy more wood. It's not cool."

Likewise, history class has a renewed relevance for Joe Leon's seniors at Fowler High School, as they put their civics knowledge to work conducting weekly study sessions for adult Punjabi immigrants studying for their American citizenship tests. For Hodges, whose Trout Go to School was the ninth such project for her, teaching this way adds relevance, not burdensome work for teachers. "To me, service learning isn't an add-on," she says. "It's not just something extra if you know the standards well enough and how to apply them."

Teachers Learn the Ropes

Hodges developed her service-learning teaching skills by attending workshops held by the California Department of Education's CalServe Initiative and through training by the Fresno County Office of Education. She also received specific instruction for Trout Go to School, along with a curriculum and trout eggs, from the state Department of Fish and Game, which designed the trout project.

Each spring, the Fowler district holds in-service classes for teachers new to the district and those who want a refresher course in service learning. The training, conducted in part by Superintendent John Cruz, defines what service learning is and isn't and gives teachers time to brainstorm projects both in their curricular areas and across grade levels.

The goal is to help teachers bolster their instruction in a way that makes sense to them. "The standards are our guidelines; the textbook is not. The textbook helps us, but we can think and develop and do it our way and make it our own," says Fremont Elementary School teacher Beth Feaver, who is also head of character education in Fowler. "One thing I enjoy seeing is that each project shows a teacher's personality." Feaver says the Character-Education Committee annually surveys teachers about interests so that schools can design professional development in support of service learning.

Though some service-learning projects require little more than imagination to get them rolling, others require extra resources. In Fowler, the Fresno County Office of Education helps the district find grants, while the schools look for community partners. Marshall's Garden Club received seeds from California State University at Fresno, local businesses and civic organizations donated money and materials, and church groups and the Boy Scouts provided labor.

The schools raise awareness -- and find sponsors -- by sharing their work at open houses and community forums, creating a kind of mobile exhibit of service learning. "We make display boards that go from school to school so everybody in the district can see all the projects that are in the works," says Feaver.

Success Breeds Success

By many measures, students are succeeding districtwide in Fowler. Since the 2004-05 school year, students have improved their scores on the state's Academic Performance Index by more than 10 percent. They now rank just below the state average. The district has a 97 percent attendance rate, and fewer than 1 percent of high school students drop out, a much lower rate than in surrounding districts with similar demographics.

Cruz doesn't credit the district's service focus with all of that success; he maintains it's but one strategy in a larger program that includes keeping schools small, providing tutoring for students, and offering fun after-school classes.

Nevertheless, Fowler's students have latched onto service. In the past few years, they have racked up a host of state and national service prizes -- like the President's Volunteer Service Award (which requires a minimum of 50 hours of service per year for students under age 15, and 100-174 hours for those 15 and up) and the Governor and First Lady's Service Award (requiring at least 25 hours of service per student under 15 each year) -- and the district has earned the California School Boards Association Golden Bell Award for Civic Education, along with other distinctions.

Still, the real impact of service learning may be harder to measure. Lea Steele's fifth-grade class at Fremont learned math and history while doing chores to raise money for holiday gifts and meals for disabled veterans and their families. She's seen service learning capture the attention of students who aren't the most academic, social, or popular.

Along with feeling connected to the veterans' families they helped, students made far-reaching friendships and long-lasting alliances in class because they got behind a common goal. "It broadens their idea of what their community is and what community means," she says.

Lisa Morehouse, a former teacher, is now a public-radio journalist and an education consultant.