The Reading Wars: Choice vs. Canon

English teachers are wrestling with how to navigate the increasingly contentious terrain between student choice and assigning the classics.

The day I arrive for the school-wide “Read-In” this past spring, teenagers and books are covering every available surface in Jarred Amato’s English classroom at Maplewood High School in Nashville, Tennessee—flung across lived-in couches, desks, and chairs. But there’s not a book one might traditionally identify as a “classic” in sight, and that’s by design.

In the middle of the room, a group of girls are cracking open the third installment of March, the graphic novel by Rep. John Lewis and Andrew Aydin about the civil rights movement, when a student pushes his way through. “Hey, get out of my way,” he says playfully to the girls, grabbing a copy off the top of the stack. “I’ve wanted to read March!”

Things weren’t always this way. Four years ago, when Amato arrived at Maplewood High, he assigned his freshmen Lord of the Flies—a staple of high school lit classes for more than 50 years—but he couldn’t get students to read the book. “It’s a classic for some reason, but I don’t know what that reason is. Because it’s not good,” says Calvin, a graduating senior, who laughed when I asked if he finished it.

Frustrated, Amato surveyed students about their reading preferences and found that most didn’t know: They almost never read outside of school and generally had negative attitudes about reading. Many students felt like the books they were assigned at school didn’t reflect their experiences, and featured characters who didn’t look, think, or talk like them.

The issue of a disconnect between young readers and the books they’re assigned isn’t new, though. Like previous generations, American middle and high school students have continued to spend English class reading from a similar and familiar list from the English and American literature canon: Steinbeck, Dickens, Fitzgerald, Alcott, and, of course, Shakespeare.

But now, as social attitudes and population demographics have shifted, teachers across the country are saying that the disconnect between the canon and its intended audience has become an epidemic, driven by rapid changes in the composition of American schools and the emergence of always-on digital platforms that vie for kids’ attention. By middle and high school, teachers concede, many of today’s students simply aren’t reading at all.

“What I saw was that the ‘traditional’ approach to English class wasn’t working for a lot of our kids,” Amato says, referring to Maplewood’s chronic low performance—fewer than 5 percent of students are on track for college and career readiness in English (and math as well). “We have a literacy crisis, and Shakespeare is not the answer.”

To Amato and a growing number of teachers, the solution has been to move away from classics in English class and instead let students choose the books they read, while encouraging literature that is more reflective of the demographics and experiences of students in America’s classrooms. In teacher training programs, in professional publications, and throughout social media, choice reading has become a refrain that can sometimes sound like dogma, and for some it has become a call for advocacy.

What's in the Center?

But while the student choice reading movement is growing, it is by no means universally accepted or supported in all classrooms. Other educators have warily pushed back on the approach, worrying that too much student choice is putting young adult (YA) and graphic novels—not highly regarded and vetted literature—at the center of the English literature curriculum. While not all books are enjoyable (or easy) to read, challenging books help boost students’ comprehension and reading proficiency, they argue, and force them to grapple with difficult, timeless questions about love, life and death, and societal dynamics.

Choice reading and academic rigor are not mutually exclusive, though. To find balance, some teachers are trying methods like allowing students to choose from more diverse, preapproved lists of challenging literature; alternating between chosen books and assigned books; or using choice to pique students’ interest in reading more stimulating texts.

Though polarizing—and at times highly contentious—the debate over reading lists in English class has illuminated the rapid pace of change in what kids are reading and the tension in trying to diversify literature without completely ditching the canon.

A Love of Reading

English teachers have long hoped that students would fall in love with the literature they taught. Mrs. Lindauer, my own English teacher from junior year in 1990, went to great lengths to demystify Shakespeare’s greatness, impersonating characters’ voices from A Midsummer Night’s Dream to make us laugh and help us understand the difficult language.

But in the years since I attended high school, many teachers are increasingly finding that students do not always develop a love of reading in English class, and a disaffection for assigned books can foster something else—a general distaste for it.

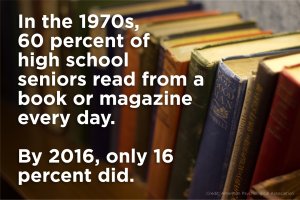

A key belief—and a passionate one—I found among English teachers is that they feel their assignments require some enjoyment to complete, a sentiment that seems to have less standing with teachers of other subjects. Educators’ concerns are also reflected in the research data, which indicates a steep decline in teens’ reading for pleasure: 60 percent of high school seniors read from a book or magazine every day in the late 1970s, but by 2016, the number had plummeted to 16 percent.

On social media, teachers are adamant about the risks of an uncritical devotion to the classics. Some teachers have argued that these concerns are especially pertinent for children of color, who are less likely to be represented in traditionally selected texts. Though U.S. classrooms are rapidly diversifying—in just a few years, half of American students will be students of color—the English literature canon, many argue, has remained mostly unchanged and mostly white.

Amato’s response to his students’ reading apathy (and the canon) was to develop ProjectLit, a classroom approach that gives students the freedom to choose and discuss the books they want to read. In just two years, the model has not only improved his students’ interest in reading, he says, but turned into a grassroots, national movement with its own hashtag (#ProjectLit) on social media with hundreds of participating schools. Other educators have also created movements of their own, like Colorado’s Julia Torres’s #DisruptTexts social media conversation.

The impact of his new approach in English class is already evident in the changes he’s seen in his students, says Amato. The 13 students who helped Amato develop the new approach in his classroom got full scholarships to attend Belmont University in Nashville this fall. In addition, 46 students from his initial class who participated in #ProjectLit scored 5.7 points higher on the English ACT and 4.4 points higher on the reading ACT than the rest of their peers at Maplewood.

The Power of the Shared Text

But there isn’t any substantial scientific evidence yet to suggest that choice reading improves reading proficiency—or even fosters a love of reading—according to some literary experts I talked to. Instead, critics warn that reading choice can be a limiting rather than expansive influence, permitting students to choose overly simplified texts or to focus singularly on familiar topics.

Doug Lemov, an educator and managing director of the Uncommon Schools charter network, tells me a story of visiting a special school for elite soccer athletes a few years ago. Looking around the room, he noticed that many students in their choice-based English classes had selected books about soccer. “They should not be reading books about soccer. All they know is soccer,” says Lemov, who, along with coauthors Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway, has written Reading Reconsidered, a book that pushes back on choice reading.

Lemov believes that student choice reading has been overhyped by schools and makes a couple of assumptions that don’t add up: First, that adolescents know enough about books to know what they like to read; and second, that there’s greater power in the freedom to “do your own thing” rather than in developing a deep understanding of what you’re reading.

Whether it’s Gabriel García Márquez, Toni Morrison, or Harper Lee, shared reading can also improve equity by giving all students access to high-quality literature, Lemov says. He also emphasizes that it teaches students to engage in a balanced and civil discourse, asserting that “you can only really listen to someone else’s perspective on a story if you’re discussing a text that you have also read.”

And though it may not foster a love of reading, the data also shows that teacher-led explicit instruction in reading a particular text (especially in different genres), combined with lots of reading, can reap four to eight times the payoff compared with students’ choosing books and reading on their own, according to Timothy Shanahan, founding director of the Center for Literacy at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Shanahan, a leader of the National Reading Panel, notes that classrooms where students have free rein over book selection can place a significant burden on teachers to know many different books well enough to guide deep analysis and interpretation of text for each student.

Finding a Middle Ground

For many teachers I spoke with, though, the polarizing debate over reading lists is making it difficult to find middle ground. In her seventh- and eighth-grade English classes at J.T. Moore Middle School in Nashville, Anna Bernstein tells me she puzzles through a thousand considerations when choosing what her students will read that year.

Bernstein tries to include a diverse array of characters and authors while getting the texts to align to both state standards and an end-of-year community service learning project. She chooses three to four texts the class will read together while leaving some room for student choice texts. Then, she considers text difficulty and genres that will stretch her students’ capabilities or open their eyes to new ways of life.

But sometimes it can seem like this constant balancing act requires her to juggle too many factors. “What’s hard right now in the English education world is there are two camps—one group that’s never going to stop teaching Lord of the Flies, and another group that’s never going to talk about that book,” she says.

Yet while the data suggests that we are failing to interest many of today’s students in reading, it seems that educators are starting to find some equilibrium between choice and a regimented list of must-reads: Shakespeare can exist in class alongside books kids want to read.

To find better balance, educators can gather recommendations of diverse books to include in their classroom libraries from organizations like We Need Diverse Books, which has partnered with Scholastic to ensure that all kids see themselves and their experiences represented in literature. Others suggest that teachers allow choice reading within tiered levels of challenge or a mix of easy, medium, and challenging texts. And Melanie Hundley, a former English teacher—and now professor at Vanderbilt University—emphasizes that teachers can “hook” students using choice books to get them excited about more challenging literature.

“If kids will read and you can build their reading stamina, they can get to a place where they’re reading complex text,” she says. “Choice helps develop a willingness to read… [and] I want kids to choose to read.”