The Power of Being Seen

How well do you know your students? In a Nevada school, a simple strategy pushes teachers to look beyond the lessons.

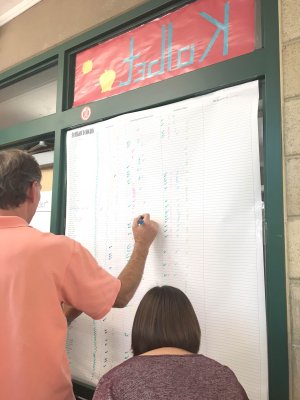

When the bell rang for early dismissal on a recent afternoon at Cold Springs Middle School in Nevada, students sprinted toward the buses while teachers filed into the library, where posters filled with the names of every child in the 980-student school covered the walls.

Taking seats where they could, the teachers turned their attention to Principal Roberta Duvall, who asked her staff to go through the rosters with colored markers and make check marks under columns labeled “Name/Face,” “Something Personal,” “Personal/Family Story,” and “Academic Standing,” to note whether they knew the child just by name or something more—their grades, their family’s story, their hobbies.

Teachers scanned the lists attentively, periodically cross-referencing information with colleagues. “Delaney is allergic to red food dye” says one teacher. “And she also has a pond she swims in,” adds another teacher, smiling. While it was only a month and a half into the new school year, some kids had check marks next to all categories—but others seemed more loosely tethered to the school, recognizable only by name and face, their lives outside school a mystery.

“This practice is the foundation of our middle school,” Duvall told the teachers, reminding them of research showing that students who don’t form meaningful connections at school may be at risk for behavior problems, dropping out, and even committing suicide. “Every student needs to belong and connect to at least one teacher or one adult in this building every day.”

This simple exercise has become standard at Cold Springs, located on the rural outskirts of Reno—an area where wild horses sometimes roam the roads and the first dentist’s office opened just a year ago. The activity pushes staff to look beyond their lessons to reflect on how well they actually know their students, driving them to build real connections that can make a difference in a child’s future. The practice is also the entry point for a larger focus on social and emotional learning (SEL) at the middle school and more broadly within the 64,000-student Washoe County district.

A District Approach

After a decade of high school graduation rates that hovered around 55 percent, Washoe school leaders realized they needed to do something different to put their kids on the path to colleges and careers.

“Two big reasons students leave school are that they have no meaningful connection to an adult in the building, and no one knows their name or how to pronounce it,” said Trish Shaffer, the district’s SEL coordinator. “This SEL work isn’t just feel-good: We know through research that relationships and connections keep kids in school.”

Inspired by data showing that social and emotional skills like perseverance and empathy can improve academic and overall student success, Washoe County launched a district-wide SEL program in 2012, adopting a mission statement of “Every Child, by Name and Face, to Graduation.” The goal was to have 90 percent of students graduating by the year 2020, or “90 by ’20,” a phrase that has become a mantra around the district.

Leveraging a grant and supportive partnership with the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)—a nonprofit organization that supports SEL programs in nine other districts in the nation—Washoe has worked to improve school climate and culture, parent engagement, and student voice in all 98 schools in the district.

An annual Student Climate Survey gauges how students feel about their school, for example, while Parent University nights train caretakers in how to use social and emotional practices like growth mindset and resilience in their homes. Administrators track students’ absences, suspensions, and truancy, assigning each student a risk level for dropping out and then identifying what SEL measures could help them before it’s too late.

In the five years since adopting the SEL-oriented approach, Washoe schools have seen higher rates of attendance and scores on state reading and math tests, and fewer disciplinary infractions and suspensions among students with higher social and emotional skills. Graduation rates have gone up 18 percentage points across the district.

Into the Classroom

For many teachers in Washoe County, the seemingly simple practice of combing through rosters can be a needed wake-up call, representing the first step toward integrating SEL practices more deeply in their classrooms, according to Shaffer, Duvall, and other Washoe administrators.

At Cold Springs in particular, it’s helped teachers to recognize that it’s not always the students they were already concerned about that need extra support.

Fifth-grade teacher Stephanie Horne realized during the library session that one of the students she didn’t know anything about was actually one of her best students—a girl who always finished her work and never asked for help.

Once teachers perceive these gaps in their knowledge of students, they’re directed to look for ways to get to know the students better based on the district’s three signature SEL classroom practices: welcome rituals and routines, more engaging or interactive teaching methods, and end-of-class reflections.

Horne, for example, has taken steps to close the distance with her high achiever since the library session. She calls on the girl more and has started conversations about the toys or stickers the girl brings to class—anything to make a personal connection. Horne also created a role-reversal math game that integrates SEL with academics, giving her reserved student, and the rest of the class, a chance to move from the periphery and talk in front of the room.

Fifth-grade teacher Kaly Krentz, on the other hand, now holds a Feel-Good Family Circle every Friday morning to promote a sense of community and belonging. Students write anonymous compliments about their peers on Post-its and put them in a box, and Krentz reads them aloud. Compliments serve to make each student feel known and appreciated within the group, and also help Krentz learn more about the students herself.

And seventh-grade science teacher Chris Ewald has found that integrating SEL practices can be as simple as a greeting. Ewald has his students line up outside his door and greets each one individually, often with a fist bump or a high five, and what he calls an ice breaker—a simple question like, “What’s your favorite flavor of ice cream?”

“I want to find out what their interests are, and that kind of opens the door. Then that moves to, ‘What challenges are you currently facing?’” Ewald said. “We are developing trust and loyalty, and then students are no longer a piece of data, but a real human being.”

Room to Grow

Before adopting the SEL strategy, Duvall says, it was more difficult for staff to get to know students and their families because their rural community is so spread out and unconnected—even, at times, antisocial. She estimates that up to half of Cold Springs students could be at the federal poverty level even though state Department of Education data puts the number at 42 percent, because some families are too proud to ask for help or don’t want to share their private information with the government.

But today, Cold Springs is seeing signs of progress: Students are attending school more and having more success in class, especially students who previously had difficulty in school or come from more challenging circumstances at home.

There’s also been a whole-school culture shift that’s gone beyond improved student-teacher relationships. Administrative staff, cafeteria workers, custodians, and volunteers are becoming more engaged and connected with students, too.

Donna Selyn, known at Cold Springs as “Grandma Donna,” for example, originally volunteered to assist teachers and office staff during the school day, but now much of her work involves the students. Often during breakfast and lunch, Grandma Donna can be found in the cafeteria helping kids with homework, settling disputes, and giving out hugs.

And four days a week, the Cold Springs Student Leadership Team, a group of 30 eighth graders, hosts games for younger students to get to know them individually and help them learn SEL skills like cooperation and communication. Eighth grader and Student Leadership Team member Moises Aguilar said that he feels responsible to set a good example of how to be a team member, while Katie Lawrence said she tries to remember not to “talk to them like a teacher, [but to] talk to them like a friend.”

There’s still work to do, says Duvall, pointing to the need to improve test scores and the results of last year’s Student Climate Survey, in which 18 percent of Cold Springs students reported that they believed an adult at school wouldn’t notice if they were absent, and 40 percent said that teachers didn’t understand their problems. Likewise, the district has to make some gains to hit “90 by ’20,” but school leaders say they “are on the right path” to get there in two years.

For teachers, it’s often less about the numbers and more about the budding one-to-one connections they’re forming with students.

Librarian Joshua Kolbet says he got to know his student aide when the shy, lanky eighth grader was just a fifth grader struggling to get along with both peers and teachers. Over the last four years, Kolbet has helped the student through challenges with bullying and learning to identify and acknowledge others’ emotions—and his own.

Now, when Kolbet hosts SEL activities in the library, that same student openly shares his social challenges with others who are struggling.

“He talks about how he feels awkward around others, but how he still puts himself out there and finds those that have commonalities,” Kolbet said. “It has been exciting to see him grow, and I know the relationships he developed within the school will help him be successful in high school next year.”