Parent Engagement in the Digital Age

Communication apps are breaking down barriers that have limited parent engagement in the past.

In school districts around the country, handwritten notes, calls home, and face-to-face meetings are rapidly ceding ground to new technologies that better meet the needs of parents and schools.

According to a 2016 report, there’s been a steep drop in the number of parents who believe that more intimate forms of communication—face-to-face meetings with teachers, for example—are the most effective means to convey important information about students. The same study found a growing acceptance of digital methods.

Sensing the opportunity, simple communication apps like ClassDojo, Spotlight, Remind, and Seesaw allow educators to send mobile texts, video summaries, and other alerts to parents about important school activities or their child’s recent academic or behavioral progress.

Taken together, these new ways to communicate are giving parents a deeper look into their children’s performance and experience in the classroom, while forging tighter relationships between schools and families. Educational apps have even played a vital role in updating parents about snow days and disasters like Hurricane Irma, while advanced features translate report cards into languages from Arabic to Vietnamese.

Digital Outreach Is Backed by Research

This growing reliance on tech-based communication is informed by research that shows digital outreach can help parents stay informed, become more involved, and be better positioned to help with kids’ schoolwork—all factors driving better student engagement and performance.

In a 2017 study from Columbia University, for example, middle and high school parents received weekly texts about their children’s grades, absences, and missed assignments, resulting in an 18 percent increase in student attendance and a 39 percent reduction in course failures. And a 2014 Stanford University study found that when parents of San Francisco preschoolers were sent weekly text messages with literacy tips they could practice at home with their children, they were 13 percent more likely to do so. The parents also communicated more with their kids’ teachers, resulting in higher literacy scores for students.

Apps are also eating away at persistent socioeconomic, linguistic, and scheduling barriers that have limited parent-school engagement in the past. According to one 2014 study, black and Latino adults who have been traditionally less engaged with schools send or receive texts more frequently than their white counterparts, and rely more on their phones—as opposed to computers—for information and communication.

“If you work a second shift as a parent, and can never talk on the phone, it’s problematic, but if you can text, that’s a game changer,” says Deb Socia, executive director of Next Century Cities and former executive director of Tech Goes Home, an initiative to help improve technology access among low income parents. “It makes it so much easier for parents to know what’s going on. I think the outcomes for families are not just that the children have parents who are more engaged, but also that parents become a deeper part of the fabric of the schools.”

While text-based parent engagement apps are multiplying, we’ve selected a few below to share their stories of success in schools.

ClassDojo

ClassDojo is a popular tool in the 19,178-student Reading, Pennsylvania, school district, located roughly 60 miles from Philadelphia.

The text-based app allows educators to update parents on student behavior, both positive and negative, as well as message parents in 35 languages. Parents also have access to School, Class, and Student Stories—a timeline of pictures and videos about their child’s experiences. Ninety percent of K–8 schools across the country are already using ClassDojo, and the company continues to grow at a fast clip: Since last year, the app has welcomed 15,000 new schools.

In 2017, the Reading district adopted ClassDojo at all schools to improve parent engagement and gain a deeper understanding of the school community.

We can’t assume we understand our community just because we work here.

According to Kyle Crater, the assistant principal of Amanda E. Stout Elementary School, most district staff members live in the surrounding suburban areas in Berks County, rather than urban Reading. The district is high poverty—more than 90 percent of students are on free and reduced-price lunch—and culturally and linguistically diverse, which has sometimes created obstacles when trying to get parents more involved, Crater explains.

“We can’t assume we understand our community just because we work here,” Crater says. “Most of our staff don’t live in the community, and when you look at the demographics of our district and staff, they don’t match up. But what we do have in common: We want all our kids to succeed.”

ClassDojo’s translation feature has been especially helpful in improving communication with non-English-speaking parents in Reading.

In Rebecca Mohler’s fourth-grade class, for example, at least half the students speak a language other than English at home. Mohler sends messages to parents about school events like Spirit Week, their kid’s homework, and positive or negative things about their child’s day. Using the app, both Mohler and parents can write in their native language and then translate the messages into the receiver’s language.

“In the past, I’ve been hesitant to call parents who I knew didn’t speak much English,” says Mohler. “With ClassDojo, I feel more able to communicate with them.”

Spotlight

A high-poverty urban district with 28 percent English language learners and more than 50 home languages spoken throughout the district, Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) in California was looking for new ways to reach these diverse families.

In 2015, OUSD decided to pilot Spotlight’s new video report card application in three schools, and within a year adopted it in 16 more.

With Spotlight, parents are texted a link to a personalized video that provides context about their child’s report card, such as a history of the child’s performance in core subjects, areas for growth, and recommendations to further support the child’s learning—like attending the local library’s reading group or using a free online math platform.

“A report card is critical information for a parent. It provides a foundation for conversation with teachers about how to make sure that their child succeeds throughout their education,” says Susan Beltz, the chief technology officer at OUSD.

These personalized video report cards can be translated into a parent’s native language—currently Spanish, Arabic, Vietnamese, and Mandarin Chinese are available.

Spotlight is piloting a number of technologies that make other data easily understandable and personalized for parents. In New Mexico, Spotlight has partnered with the state Public Education Department to test a video that explains how a school compares with other schools in the state in relation to things like suspension and graduation rates. The video can be translated into English, Spanish, or Navajo. Spotlight plans on expanding these applications to more districts in the future.

“The value here is really about breaking down those barriers to parents who may not have time to get to school, who may not have the means to access an online portal, and who may not speak English,” said Mike Fee, the founder of Spotlight. “This is about more than just providing information. It’s about reaching people where they are most comfortable.”

Remind

In rural Groton, New York, Groton Elementary School is using Remind to build a bridge to parents who feel disconnected. The application allows educators to send one-on-one, class-wide, and school-wide text updates to parents.

“I don’t believe that every parent necessarily has a lot of trust in schools. They haven’t always had good experiences,” explains Kent Maslin, the principal of Groton Elementary. “You get some people who are discouraged, who didn’t feel like the school understood them. They didn’t see stuff that looked and felt like their cultural or life experiences.”

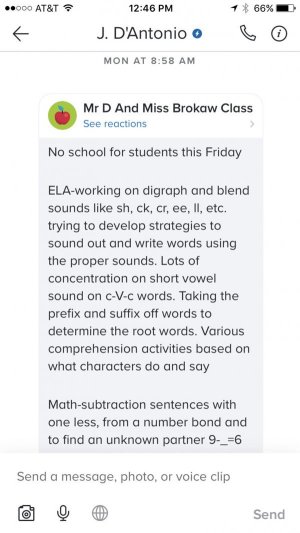

Teachers text weekly updates—which can be translated into over 70 languages—about what their students are learning across all subjects, photos of students in class, and ways parents can help with homework. Educators can also see who reads the messages and who they might need to follow up with through another medium.

“Remind really opened up communication in a positive way,” says Kelly Neville, a second-grade parent. Previously, Neville says, she would receive notes in her daughter’s folders about once a week that would sometimes get lost. Now she gets instant, almost daily communication directly from the teacher.

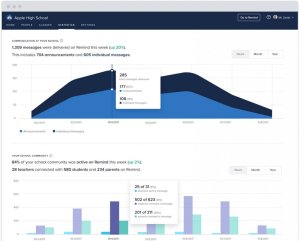

Remind is currently being used in more than 70 percent of public schools in the United States, and claims 23 million active users. Though it is free for teachers, Remind is expanding to meet school and district administrators’ needs through a paid plan, which adds features like communication logs and district engagement reports.

While Remind has been adopted school-wide at Groton, not every teacher chooses to use it. Jennifer MacDonald, a pre-K teacher with 34 years of experience, uses Remind to update parents about upcoming field trips, for example, but when it comes to sharing what’s going on in the classroom, she still prefers sending out a paper newsletter. MacDonald believes this traditional method includes more context than a Remind update does, or a young child could provide.

“I think that it really depends on age. I see the younger teachers are really excited about using Remind,” MacDonald says.

Seesaw

Daniel Whitt, the coordinator of instructional technology in the Madison City School District in Alabama, says his district started using Seesaw—adopted in more than 25,000 schools, 200,000 U.S. classrooms, and over 150 countries—to showcase learning practices in the schools.

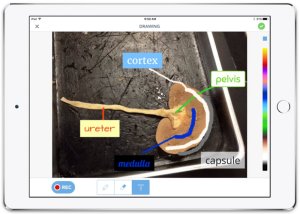

The app allows kids to explain their learning to their parents, and parents can respond directly during class time. Students might record a video showing what they’re working on and their thought process behind it, or take a photo of their work and add audio to narrate their thinking. If approved by their teacher, a text will be sent to their parents, and their parents can reply with questions for their child. Some teachers use Seesaw more like a newsletter to capture student learning themselves to send off to parents.

Melissa Miller, a Mill Creek Elementary teacher in the Madison City district, initially used the app to flip her classroom—providing parents with easy access to videos that would prepare her kindergartners for the following week’s lessons. She’s recently expanded her use of the app: She’s now also using it to help students demonstrate their learning—and despite their very young age, they’ve picked up on how to use it quickly, she says.

Parents say they also feel more connected to what’s going on in the classroom since the district started using Seesaw.

“Seesaw keeps in me the loop,” said parent Paige Novack. “My daughter doesn’t always like to talk about what she did in school, so the pictures and videos give me some idea. It also helps us know what she’s doing well in and what she needs a little work on at home.”