If You’re Not Failing, You’re Not Learning

The learning scientist Manu Kapur, architect of the theory of productive failure, on reframing our notion of failure, and letting kids stumble with purpose.

The urge to jump in and fix things when students struggle is instinctive—but sometimes our best intentions put us on the wrong side of learning.

“I think good teaching happens when you control that impulse,” says the renowned researcher Manu Kapur, father of the theory of productive failure. If schoolwork is curated to ensure that kids never feel confused, frustrated, or lost, then they’ll never learn to deal with emotions and feelings that are part and parcel of everyday work. “Being frustrated and struggling are normal things,” Kapur insists. “In fact, if you’re not feeling those things, that means you’re probably not learning.”

Kapur, a professor of learning sciences and higher education at ETH in Zurich, Switzerland, knows a thing or two about failure, and has built his career on understanding the dynamics of durable learning. As a young graduate student, he noticed that the prevailing approach among educators was to design lectures that were informative and easy to understand—with good, clear instruction comes good learning, the conventional wisdom held. Even today, that pedagogical assumption underlies many of our curricular decisions.

Yet when athletes hone their skills, Kapur noticed, it’s messy, and frequently involves failure and frustration. “People intuitively understand that if you want to learn how to play football or tennis or any other sport, that it's challenging,” says Kapur, who was a professional soccer player for an early stretch in his career. “You will struggle, you will fall down, and you will sometimes win and sometimes lose.”

Somehow that all changes when you’re learning math, or working your way through a challenging novel. Everything is supposed to be positive: “If you struggle, that's not good. If you are feeling frustrated, that's not good.”

If trying and failing is so instructive, Kapur reasoned, why don’t we intentionally design for it in schools? It was a radical but logical deduction. Developing the learning theory of productive failure would become Kapur’s signature contribution to the field of education, gaining widespread acceptance in K-12 classrooms around the world, including by the high-performing Singapore school system which integrated the concept nationwide into its pre-university math curriculum and pedagogy.

We sat down with Kapur to talk about how to integrate productive failure into the classroom, the downside of over-reliance on direct instruction, and why we should be normalizing failure in schools.

Youki Terada: Many teachers are familiar with the concept of productive failure, but as the theory’s founder, can you explain what it is?

Manu Kapur: For a very long time, we believed that we learn poorly from bad teaching—and that’s obviously true. But we actually learn very poorly from even very good lecture-driven instruction: retention is poor, understanding is poor.

So how do we solve that problem? How do we truly prepare the novice learner?

It’s an epiphany of my doctoral studies: If success doesn't work right off the bat, then maybe we question that very assumption and design for failure, giving students problems that we know they will not be able to solve, but creating opportunities for them to explore and generate potential solutions. That creates a very powerful incentive for them to then learn the material correctly from a teacher. It's that sequence that turns the initial failure into something that is productive and that, we find, is very effective.

Terada: Specifically, what does designing for failure look like in a classroom?

Kapur: In a productive failure lesson, teachers will typically use carefully designed problem solving activities based on productive failure principles, instead of jumping straight into instruction.

These problems should be just beyond students’ reach—they’re designed in ways that will activate prior knowledge and motivate students, clarifying what they know and what they don’t know. If the challenge hits that sweet spot, that’s where deep learning happens.

In the process of trying, students may generate ideas that are completely incorrect; they may create possible answers in multiple representations and modalities, but, as expected, they never quite get to the correct solution.

Typically, that might go on for about 35 to 40 minutes. And then the teacher steps in, ideally builds off of students' ideas and solutions, compares and contrasts them, and then teaches the correct concept.

Terada: Still, you’re very clear that failure alone is not instructive.

Kapur: Right. If failure alone was instructive, then discovery learning would work. If I propose a solution that doesn’t work, or comes close to a correct or optimal solution, that doesn’t mean I'll ever discover the canonical solution by myself.

We don’t want students to flounder. Failure helps in building awareness and learning affect—the desire to learn—but in and of itself, it cannot get you to assemble knowledge, which is the process of integrating new information with the activated prior knowledge. A teacher or expert is needed at that point to explain the problem and solution.

The goal is to design experiences that incorporate failure in a safe, curated way. Then, we turn that initial failure into something that is productive by stepping in, giving students feedback and guidance, and helping them to make sense of the material by assembling it into a more coherent whole.

Terada: Let’s talk about the evidence behind productive struggle. In 2021, you published a comprehensive meta-analysis—encompassing 53 studies. How effective was productive failure as a strategy?

Kapur: Surprisingly, very effective.

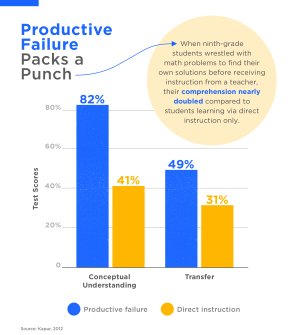

Just to give you a sense, we can benchmark effect sizes, so the idea is to quantify how much you learn from a good teacher in a year. Let’s say one unit of gain from a good teacher; that's a good benchmark in education. On average, productive failure gives you twice that effect.

But when teachers take any model and implement it in a classroom, it doesn't mean it will get implemented perfectly, in a way that’s true to all its principles. There is a question of fidelity: Sometimes fidelity is very low, sometimes it's average, and sometimes it's high.

If enough teachers persist and increase the fidelity of productive failure strategies to a high level, then they can achieve up to three times the effect.

This made big news in The New York Times and other places, because we’re not talking about a 10 or 20 percent incremental improvement. It's a real breakthrough effect.

Terada: There's a longstanding debate about whether new concepts should be taught via direct instruction or through problem solving. Why do you think direct instruction is the default mode in so many cases?

Kapur: There was a time when, as an overreaction to behaviorist pedagogies, we moved towards open-ended, discovery learning where kids try to figure things out on their own. But throwing students in the deep end and hoping they'll discover what’s taken scientific communities years to develop doesn’t work very well. So I think the response to that was, "No, we can't leave people to discover things on their own, we need to tell them exactly what to do." And so the theory of direct instruction was born—the objective was to tell learners exactly what to do and how to do it.

With productive failure, we're trying to marry the best of both approaches in a very curated, constrained way. It's not pure discovery, it's failure-based exploration, followed by instruction that builds upon it.

I think it's met with a lot of resistance because starting with problem solving in general—even very well-designed, curated problem solving—is still really frowned upon. One of my first papers took almost two years to find a home in a journal.

Terada: Obviously, kids can’t be experiencing failure all the time. How often should students engage in work that elicits frustration? What’s the right mix?

Kapur: Much more than they currently do, because any kind of knowledge work, any kind of challenging problem requires a certain level of frustration.

People in real work get frustrated all the time: Things are uncertain, things are new.

That doesn't mean students should be doing it all the time, right? In my work with schools and universities, I say: If you're going to adopt productive failure in math or science or language, don't do it every week. Instead, think about where productive failure is really helpful in terms of understanding and transfer. So in a semester, there are probably three to five big ideas you want students to really deeply understand. For those ideas, design productive failure activities; use it surgically where there are important ideas to learn.

As students engage in productive failure, set the expectations that being frustrated and struggling is normal. So flip the expectations; I think that's key. And if you do it long enough, when students are stuck, for example, or they struggle or they're frustrated, instead of giving up, the signal is, “Okay, maybe I'm in the right space now. Maybe I need to adapt." That's the kind of competence, or skill set, that you want students to develop.

Terada: So let's dig into that a little bit more. You say you want students to be comfortable with frustration and failure in ways that are productive in the long term. Can you talk about that?

Kapur: I can learn a math concept in the order of minutes or tens of minutes. But if I want to change somebody's ability to deal with uncertainty, or their willingness to persist, that takes weeks, maybe months, maybe even years.

So if you carry out productive failure for just one topic for one week, you're not going to get the benefits of these longer timescale effects. You're only going to get the short timescale effects on knowledge and understanding and transfer. But if it can be integrated in a meaningful way into the curriculum in a school, then these longer term timescale effects will come into play.

Terada: For many students, failure is associated with negative emotions like shame and rejection. How can teachers reframe that?

Kapur: We're talking about failure that's intentionally designed in a safe way. We’re not talking about high-stakes failure, like from an exam. When students are stuck, they feel all sorts of emotions—shame, guilt, and frustration, for example.

Our research has shown that if you think positive emotions are always positive for learning, and negative emotions are always negative for learning—that’s not true. The emotional dynamics in productive failure are far more complex. Take the child through this roller coaster ride in a safe explorative way so that they experience it, and then they have a teacher to guide them through it. And over time they learn how to deal with it, and that's when they can derive the most powerful effects of productive failure.

We want productive failure to be the norm, so that instead of thinking, “I suck at this," they’re thinking, “Okay, I'm stuck. This is normal. I need to do something about it."

This interview was edited for clarity, flow, grammar, and length.