Teaching Kids to Give and Receive Quality Peer Feedback

Building a classroom culture of feedback requires scaffolding and a safe, nurturing environment, but it’s worth the effort, teachers say.

Jamie Kobs knows the value of giving students timely and meaningful feedback, but she often struggled with the volume of incoming assignments. Then she discovered a solution: her students. Feedback didn’t always need to come directly from her, the veteran high school English teacher realized. In fact, if she taught kids the skills to deliver constructive, focused feedback, it could be equally meaningful coming from fellow classmates.

“Besides relieving me of some of the pressure, creating a classroom culture where students give each other feedback has helped me increase engagement and build community,” Kobs says. “Having more frequent interactions among students builds rapport and trust and disrupts the idea that I’m the only expert in the room."

A high-functioning feedback culture also frees up teachers to give more low-stakes assignments, creates more opportunities for students to practice, and democratizes the creative process—replacing the top-down dynamics of more typical classrooms and making kids an equal and accountable part of learning outcomes for everyone. Kids who frequently draw, create podcasts, or write fiction with the expectation that their peers will be consuming it, and who are themselves expected to provide useful feedback, are more likely to be attuned to the elements that make art or stories truly outstanding and “feel more seen, heard, valued, and, consequently, engaged in their work,” according to Kobs.

But the middle and high school years can be a difficult time for students when it comes to peer evaluation—some initial reluctance is normal. Research shows that adolescents are hypersensitive to criticism, and when they feel judged, they can become self-conscious, stressed, or withdrawn. Other students may feel tentative or shy about giving feedback to peers they admire, and for English language learners, the process might feel especially daunting.

Developing a culture of feedback must therefore happen in tandem with creating a safe and supportive classroom. By scaffolding the feedback process in a classroom where kids feel valued and empowered—the effort requires “consistent modeling, repetition, and a commitment to sharing the feedback with students,” says Kobs—even teens can become more comfortable with the act of giving and receiving peer feedback.

Here are six considerations for creating a culture of feedback in the classroom.

Encourage reflection, not correction: Consider limiting feedback cycles to work products that are not highly structured, or that require granular feedback related to syntax, grammar, and spelling. When students in Mark Gardner’s high school English class provide feedback, he encourages them to focus on collectively reflecting, not correcting, each other’s work. Very few incoming high school students have mastered the conventions of writing well enough to be reliable copy editors, he says. Rather than correcting syntax errors, Gardner wants his students to focus on providing feedback that outlines clear next steps that peers can take toward improvement.

“My students focus on idea development, clarity, and arrangement to make sense of the writer’s text,” he explains. He asks students to write full sentences in their observations like, “I am confused about who ‘they’ are in this sentence” or “I like how you repeated keywords from your hook here in your conclusion.”

Assign feedback partners: To prevent students from worrying about evaluating friends, high school history and government teacher Benjamin Barbour recommends assigning partners instead of letting kids choose who to critique in the class. Once students are working in pairs, consider allowing them to share feedback with each other rather than with the whole class, making it a generally less stressful experience for kids.

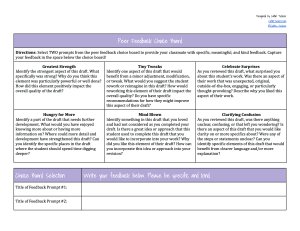

Offer choices: Including an element of choice in the feedback process can build student agency and motivation, writes educator Dr. Catlin Tucker in her blog. A peer feedback choice board, for example, allows students to select prompts that provide direction and context for delivering feedback that’s “specific, meaningful, and kind,” Tucker notes.

For English language learners, teachers can create choice boards “with sentence frames to provide students with additional support as they give each other focused feedback,” Tucker writes. “For example, under the box labeled ‘Greatest Strength,’ teachers could rework that as a series of fill-in-the-blank statements. The strongest part of this draft was ______. I thought ______ was done well. I really liked ______.”

Deliver feedback that is specific: Emphasize the idea that criticism must be both constructive and specific in nature in order to be helpful. English language arts specialist Katherine James says that students often leave general or vague feedback like “I really enjoyed your story.”

Instead, encourage kids to be focused and specific with their feedback. “Give examples of what specific feedback sounds like—for example: I really liked your simile ‘the rain hit the pavement like arrows’ because it helped me visualize the setting,” rather than the more general ‘I liked your description,’” James says.

Specificity counts in oral feedback too, and scaffolding student responses is equally important. After Socratic seminars or academic discussions in her classroom, Kobs directs students to “give a specific example of something someone else said during this discussion that resonated with you,” and “explain why it stuck with you.”

Model feedback, and suggest sentence starters: During the brainstorming stage of a personal narrative assignment in her high school English classroom, Kobs’s students pitch ideas via Flipgrid videos. Students then watch and respond to the pitches of two classmates with the help of sentence starters.

To ensure that the feedback cycle is targeted and productive, Kobs and her colleagues “model both the pitch and the response steps with videos of our own” and provide sentence starters to help kids focus on the most important aspects of the piece and clarify how to deliver their feedback. Sentence starters might prompt students to say, “I didn’t get the part about...,” pose questions or suggestions out of curiosity like “What happened next?” or “Maybe you can try...,” or make connections: “Something similar happened to me when...”

Prompt deeper engagement: Consider trying an “I like, I wish, I wonder” framework as another way to help focus students on content rather than grammar and spelling errors. It encourages them to interact creatively with their peers’ work, says James, and encourages critical thinking as students try to provide meaningful feedback.

“When reading each other’s work and giving feedback, they must discuss one thing they liked about the other person’s work, one thing they wished that person had done differently, and one thing they wondered about (for example, how a main character felt about or reacted to an event),” she explains.