Locked Away: The Toll of Mass Incarceration on Students

Children with imprisoned siblings or parents often suffer silently, but schools can help students confront the stigma and trauma.

By the time she reached high school, Bianca Lopez had been labeled a “bad student” for talking loudly and talking back in class.

Now an adult reflecting on her years of schooling in Los Angeles, Lopez, 21, said her misbehavior masked the pain and grief she felt after her older brother was sent to prison just shy of her 12th birthday. Lopez remembers carrying the distress of her sibling’s absence to school daily until she attended a lunchtime group for youth impacted by incarceration during her junior year.

Along with the ham sandwiches, she found a sense of belonging and safety among her peers in Pain of the Prison System (POPS), a high school club for teens struggling with family incarceration. When the group handed Lopez a piece of paper and pen to write, she was hesitant at first. But with gentle prodding from the group leader, she started writing a letter to her brother. It was their first communication in over six years.

“I just poured my feelings into that letter, and it took me days to finish, but I did it,” Lopez said, acknowledging the emotions she had buried for years. From that day forward, support through POPS helped change her outlook on school; she went from seeing it as a place where no one cared to one with peers she could trust. “Knowing so many other people in the same situation was heartwarming, like you’re not alone.”

Though seldom discussed, the vast reach of mass incarceration, and the corresponding toll on American children and families, is well documented. In a 2018 survey of more than 4,000 adults, researchers found that nearly half reported having an immediate family member currently or formerly incarcerated—for one in four, a sibling; for one in five, a parent. For children, the impact is particularly severe. One in 14 children has had an incarcerated parent—there are more than 5 million children affected today—and about half of children with incarcerated parents are under the age of 10.

The scope of the racial disparity is even more staggering: Among black children, one in nine has experienced parental incarceration, a rate twice that of white children. And among black youth aged 12 to 17, nearly one in seven has a parent who has spent time in jail or prison. Additionally, black and Native American women—the majority of whom have been charged with low-level, nonviolent offenses and never convicted—are overrepresented in the country’s jails and prisons. And many of them are mothers: An estimated 80 percent of women in jail have children.

These sobering numbers have significant implications for America’s classrooms—where children spend the bulk of their day—and make it unlikely that there’s a public school in the country without impacted children. Like Lopez, many youngsters suffer silently with the emotional trauma of family incarceration as most educators are ill-prepared to support them, leaving children feeling isolated and ignored.

Breaking the cycle of invisibility is painstaking and vital work for educators that requires a change of heart—and mind—to meet this vulnerable population’s unique needs.

Shame, Stigma, and Silence

For teens with loved ones in prison, finding a safe haven in schools was tricky before POPS launched in 2013. The program, now in 17 schools across the country, is modeled after the Gay-Straight Alliance clubs that formed in the 1980s to provide support for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) students. Piloted at Venice High School—Lopez’s alma mater—POPS provides a safe space for youth to shed the veil of secrecy through writing.

By creating a trusting environment in his classroom, Dennis Danziger, a 24-year veteran English teacher, helped students with an incarcerated loved one open up about their experiences in essays and poetry. Subsequent one-on-one conversations with his students were the catalyst that later led him to create POPS with novelist Amy Friedman, who has written about the struggles of those behind bars.

Quite often, Friedman says, teachers and administrators put on blinders, adding to the shame and stigma that shroud imprisonment. But recognizing that the issue exists is the first step to creating change, she said.

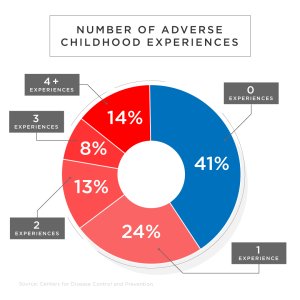

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), parental incarceration is recognized as one of 10 adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) that can lead to poor impulse control, poor concentration, and poor judgment in children, along with health and emotional impacts in adulthood. While the ACEs research and student trauma are more widely acknowledged in schools today, children with incarcerated parents are seldom prioritized in schools’ trauma-informed resources, say experts, and their isolation compounds the harm.

Combating the silence can be challenging, though. Caregivers may not tell a child the truth about a loved one, or may tell them the truth and insist they keep quiet.

Opening communication channels is further complicated by teachers’ expectations of children of incarcerated parents. Studies have shown that parental incarceration shapes how educators view and characterize children—rating a child whose parent is in prison as “less competent” behaviorally, academically, and socially. A case study of school counselors published in the Professional School Counseling Journal also cited educators’ negative perceptions as a challenge to meeting children’s needs.

“Most people think that children are ashamed of the parent or the crime, but the fact is they’re ashamed and stigmatized by the reactions of the people around them,” said Ann Adalist-Estrin, director of the National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated (NRCCFI), an organization housed at Rutgers University-Camden in New Jersey. “One of the things we know about trauma is that when people can talk about a traumatic event, the impact is less severe, and we’re not making it safe for kids to talk about it.”

Best Practices

A core element of NRCCFI’s work in schools for the last 30 years has been tackling educators’ biased attitudes and assumptions—particularly, helping them understand the intersection of mass incarceration with race, class, and ethnicity, and how their school practices and policies may hinder children and families of the incarcerated. Trainers from the center say educators may consider children with incarcerated parents the chief culprit when things go missing in their school, or respond with embarrassed silence when a child talks about their parent.

Guidance for schools is found in listening to those closest to the issue.

Young people from Project Avary, a Northern California nonprofit serving children with parents in prison, advise educators to refrain from asking the details of a parent’s arrest and focus instead on the child’s emotional reaction (confusion, sadness, or anger) to the parent’s absence; to be sensitive in word choices (using “caregiver” or “family member” rather than “mom” or “dad” to minimize discomfort); and to listen to children of incarcerated parents from a place of care and concern, rather than judgement.

Similarly, in Dorchester County on Maryland's Eastern Shore, social workers convened focus groups and conducted surveys to build trust with families impacted by incarceration, and held in-service trainings in schools to help normalize discussions on incarceration. One of the biggest takeaways was that it’s critical to respect the parent-child relationship (when clinically appropriate) and keep them as involved as they can be, said Mindy Black-Kelly, a social work supervisor for the Dorchester County Health Department.

“Children want to know that their incarcerated parent is OK. The abrupt loss of that parent from the home is often far worse than what a child will experience by having some form of contact,” she said.

Understanding this need, the Washington State Department of Corrections has collaborated with the state education department and local school districts to provide parent-teacher teleconferences for more than a decade.

About 90 phone conferences were completed during the 2017–18 school year, timed to regularly scheduled parent-teacher meetings in the fall and the spring. Participation is open to any parent in the state’s 12 prisons, regardless of classification in a minimum or maximum security facility, because “it’s not seen as a privilege for the parent, but a necessity for the children,” said Carrie Kendig, family services program manager for the corrections department, who sees reciprocal gains for parents and children.

Making Students Feel Welcome

Even small efforts by educators can have a large influence on youth impacted by incarceration.

The National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated suggests acknowledging the topic through writing prompts, research projects on the criminal justice system, and even math lessons.

Experts also say a well-tested tool for making schools feel safe and welcoming is adding books about incarceration to classrooms and school libraries. Missing Daddy, a children’s book by Mariame Kaba, profiles the emotions a little girl feels while her father is in prison, and Visiting Day, by award-winning author Jacqueline Woodson, follows a girl and her grandmother as they prepare for the girl’s once-a-month visit with her incarcerated father.

But finding children’s literature that covers the topic in an affirming way can be tough.

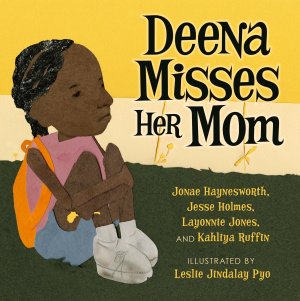

Kahliya Ruffin, 17, noted the lack of books about the lives of kids with incarcerated family members while tutoring elementary-age readers in Washington, DC. She and three friends wrote Deena Misses Her Mom—a picture book featuring a little girl’s emotional struggle after her mom goes to jail—to reflect the reality of the children they knew. It’s now available in visiting rooms in jails around the country.

“In our community, having an incarcerated parent is a conversation that’s rarely brought up,” said the Anacostia High School senior. “Kids shouldn’t be left to deal with this by themselves.”