An Alternative to Warm-Up Problems

Starting math class with a warm-up problem is common. Here’s how one teacher starts with a little chat instead, before moving on to the math.

For 14 years I began my high school math classes the same way every day: with a warm-up problem.

Most teachers know the drill. I would stand at the door, Harry Wong style, and greet students by name. They would walk into class, get their materials out, and cast their eyes to the front of the room. My warm-up question would pique their curiosity, and they would begin to work. By the time I came into class, they would have begun their mathematical journey for the day, and we would jump right into our lesson.

Except it never worked that way.

What really happened was that of 30 students, maybe five of them would diligently engage in the problem. The rest would delay in tactics ranging from pencil sharpening to grabbing a few extra winks. I would walk in and have two choices: go over the warm-up problem for less than 20 percent of the class—typically the 20 percent that didn’t need it in the first place—or waste time for the on-task students by giving the less proactive students a few extra minutes.

From Warm-Up Problems to the Cold Open

Online teaching threw a wrench in my lesson plans; I figured, “Why not try something new?” Inspired by Jessica Kirkland and her Twitter-famous use of “attendance questions,” I created a new routine for the start of class.

I ditched the warm-up problem in favor of the cold open.

I teach eighth grade now, and we’re fully back in the classroom, but I haven’t gone back to my old ways. I love my cold open—which is always followed by a related question—and my students do, too.

I still stand with Harry Wong outside the door, smiling and talking to students. I’m looser than before, because now I’m not worried about whether they’re on task in the room. They walk in and glance at the board, which looks like this: The message changes slightly from day to day, but it’s always a throwaway line: “Wednesday? Wow! Halfway through!” or “Test next week? Probably!” Something to generate conversation but nothing they can’t miss.

I enter, and instead of arguing about getting started, I just slide the screen to a short agenda. It’s deliberately vague, intended only to give them a sense of the day without bogging us down. I’m not starting math class yet; we still have to get through our cold open.

You know about cold opens if you’ve ever watched Saturday Night Live or The Office. At its best, the cold open is both entertaining and a non sequitur. On SNL, it takes place before the guest host comes out; similarly on The Office, it often doesn’t connect to the larger story. I try to operate my class the same way: The cold open is nothing more than a fun conversation starter.

It might be a picture of my dog. It might be a trivia question about the top five fastest land animals. It might be a model of the solar system showing how the tilt of the Earth generates seasons. It might be a fact about the current date throughout history. It might be a picture of a spider that I found outside the gym.

After the conversation dies down—and it might last 5 seconds or 50—I move on to the attendance question portion of my opening. To be honest, I have already taken attendance in my mind and will enter it later; I won’t stop the flow of class here. I still call it an attendance question, however, because that’s what we called it during the first week of class—when I used it to help learn names.

Choosing Attendance Questions

At its best, the attendance question connects to the cold open, like on the day of the spider picture. It lets me share something about myself and opens the door for my students to share a little bit with me. If I show a picture of my dog, I can ask about their pets. If I ask about the fastest land animals, I can take a vote on whether they think Usain Bolt is faster than an ostrich. (Spoiler alert: not even close.)

Sometimes, though, my question has nothing to do with the cold open. You get a free doughnut or a free bag of chips: What do you choose? Sing and Sing 2: They’re kids’ movies but you secretly love them, right? Peanut butter: Amazing, nasty, or mid? For a list of wonderful attendance questions that can arise from the ether, I’ll direct you again to Jessica Kirkland.

This whole process takes about 5 minutes. Sometimes, like on spider day, it lasts a little longer because I have an amazing story about an encounter with a spider the size of my fist. But I find that just about any investment in actual conversation—whether it’s about doughnuts or spiders or the ramifications of this being the one-year anniversary of the U.S. pulling out of Afghanistan—will pay off mightily in the long run. Nowadays when I begin the math, we hit the ground running. All I’ve missed is the time when I used to wheedle them to “do the warm-up problem, please.”

And yet, I’ve added a wonderful piece to my classroom pedagogy: I know my students better than I did in years past.

Students routinely tell me the opening is their favorite part of class. If I have to skip it for some reason, they cry foul. They suggest bits and sometimes help with content. As a teacher of most people’s least-favorite class of all time—eighth-grade math, yikes!—I don’t take it lightly that students say they enjoy my class. After all, happy students are far more likely to take my word that linear equations might just matter to them someday.

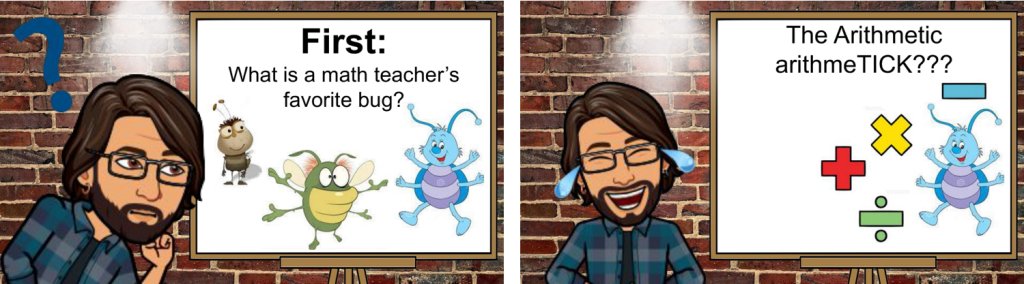

The great thing about the cold open is that it is malleable to the personality of the teacher. We’re all doing slightly different things but toward the same end: student engagement. I’ll leave you with one of my best cold opens: the terrible math pun. You’re welcome.