Setting Up Libraries to Be the Best Space in School

We took a peek inside school libraries across America to see how librarians are reframing the space to support students’ social, emotional, and creative growth—while still prioritizing excellent reads.

On any given day, more than 500 students visit the library at Campbell High School in Smyrna, Georgia—often before the school day even begins or during their lunch period.

In other words, students are choosing to spend “what little unstructured time they have,” inside the library, says Andy Spinks, one of the school’s two library media specialists.

The recently renovated library—now known as the Learning Commons—is a bright, spacious multipurpose hub within the school. There are bistro tables where kids can work together; comfortable and flexible seating; a makerspace where students can explore activities like sewing and jewelry making; an audio recording and production studio; and a video production studio where kids can create TikToks or YouTube videos using their phones or school-issued laptops. It’s a far cry from the space it used to be—an attendance sheet from 2008 tracked just 21 students signing into the library one day.

“It’s a place where students come together, interact, and build community,” Spinks says. “I often hear adults complain about teenagers ‘always looking at their phones’ and not being able to interact with people face-to-face, but that’s not what I see. I see them talking, working on group projects, playing chess and Uno, and exercising their creativity in collaborative ways. Even their screen time—playing video games, making videos, and recording music—is collaborative.”

Spinks and other like-minded librarians across America are transforming school libraries from staid, silent repositories of knowledge into vibrant spaces that welcome kids and encourage “exploration, creation, and collaboration,” writes researcher and former teacher Beth Holland. Through careful planning and with the help of student input, the Campbell High School library, and others like it, offer a critical escape from the hurly-burly of the day, serving as a nucleus of support for all manner of social, emotional, and creative needs—while still providing access to good books.

To get a sense of how schools are rethinking libraries, we spoke to librarians and library media specialists around the country about the creative ways they’re making libraries among the best places to be in school.

Putting Kids at the Center

At A. P. Giannini Middle School in San Francisco, almost half of the books brought into the school’s collection come from student requests, says teacher librarian Shannon Engelbrecht. “If a kid comes up and says, ‘Do you have this book?’ and I say, ‘I don’t have it; fill out the request sheet,’ we’ll have it in a week through the quick order system.” The same is true of the makerspace, mostly stocked with items kids ask for, purchased from a budget provided by the PTA.

“I’ll go to the Dollar Tree and see if they have pom-pom makers so that what we have in the maker center is what students have requested,” Engelbrecht says. “Then they are much more likely to want to read a book or to recommend it to their friends and say, ‘Hey, I chose this book for the library. You should give this a try.’ Or ‘Have you ever tried a pom-pom maker?’”

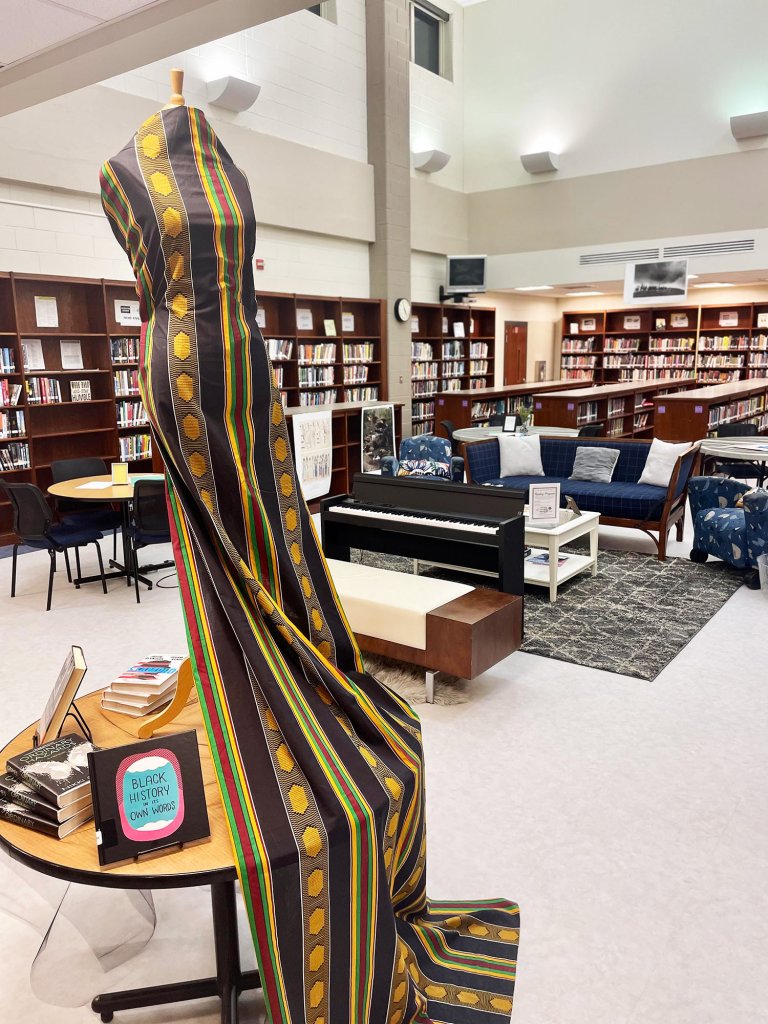

After completing a student needs assessment, Washington, D.C.-based librarian Christopher Stewart started making small changes to the school library, displaying fabrics and art connected to students’ various cultures, for example. “I want them to be a part of it,” Stewart says. “Ordering African American fabric [to display on dress forms], ordering art from Mexico that represents the students. It’s not just enough to have the book collection that is representative. I wanted to make sure that students see themselves not only in the pages of the books but also in the furniture, the art.”

Stewart also hires students to act as “library brand ambassadors,” functioning as a sort of market research panel with input on the library’s book collection, types of programming they’d like to see, and selections for book club, among other things. “It’s beautiful because they are the ears for their peers,” he says. “It’s showing intentionality on the library’s part. Because I don’t want to give you what I think you should have; I want to give you what you want and need.”

Reframing for Creativity and Even Some Noise

Libraries in the Herricks Union Free School District on Long Island, New York, aren’t always quiet—and that’s intentional, says Michael Imondi, the K–12 director of ELA, Reading, and Library Services. The days of whispering between the stacks are long gone, and when the district decided to refresh its libraries, the design priorities focused on four Cs—communication, collaboration, creativity, and critical thinking. “This is not a quiet space,” he says. “This is a working space, a collaborative space.”

There are large tables to encourage student collaboration, as well as silent study rooms where kids can work independently. In the middle school library, some tabletops are whiteboards you can write directly onto when planning group projects or mapping out thinking. A small tweak to the framing—from library to Library Learning Suite—helped emphasize the new focus. “Words matter,” Imondi says. “Having that word ‘learning’ in there, it’s important because that’s what’s happening now. Whether you’re coming to read a novel off the shelf or you’re using our 3D printer to build something for your science class, it’s a learning space.”

At Campbell High School’s library, Spinks says one of the big shifts in recent years concerns the fundamental role of libraries as spaces “primarily concerned with the information that students receive.” Now they’re “shifting more focus toward making things, producing information and media.” One of those areas is the creative arts: Spinks was surprised at the well of talent that students exhibited in the library’s audio and production studios.

“These kids are so talented, they’re so creative,” Spinks says. Originally he thought the studio might not get much use during the school day because students would need an hour or two to get anything done. But they keep surprising him with what they’re able to accomplish in short snippets of time: “They come in, and during a 25-minute lunch block, they can load up the beat, freestyle over it, and have something to share with their friends.”

Libraries Where Kids Let Their Guard Down

After noticing that students needed a “space that was their own” where they could safely process their emotions, Stewart created a peace, love, and meditation room inside the library. “It is the hub,” he says. “A place to not feel judged, to feel so much love, and to feel warm.” A welcome and necessary respite from the stress of the outside world with calming music and a water feature, it also doubles as a venue for restorative justice sessions as well as an open room that counselors and therapists utilize to care for the needs of the school community.

Carving out a judgment-free zone inside the library is also a priority for Engelbrecht. Need to use one of the desktop computers to finish your homework before class? That’s not a problem. Having trouble keeping your eyes open? Engelbrecht doesn’t mind if students occasionally doze off on the big U-shaped couch in the center of the room—it holds around seven kids sitting, and she won’t tell you to keep your feet on the ground. “You never get to do that at school because you’re not supposed to put your feet on the furniture,” she says. “But we have three pieces of furniture specifically for putting your feet up.”

Still, judgment-free doesn’t mean lawless, she says. Engelbrecht sees every English class once a month and teaches different lessons on media, technology, and digital literacy and citizenship. Her motto is “Assume best intent, equity of space, kind heart.” The conversations she has with students about everything from cyberbullying to how to respond when someone makes you uncomfortable are crucial to creating trusting relationships and establishing the library as a safe haven.

Meanwhile, in states where book bans are in effect, we spoke with librarians who are finding ways to keep their spaces welcoming and inclusive—via, for example, book displays that highlight different cultures, values, and identities.

“Every child deserves to come into the library and find a book that has somebody who looks like them, or acts like them, or has some similarity to them,” says Jamie Gregory, a librarian in a private school in South Carolina. “I think it’s important that our library collection reflects our community, but it should still be diverse, so students can learn that there aren’t people to be afraid of or who are out to get them. Every type of community deserves fair representation.”

Books Are Still the Bomb

No matter how much libraries evolve, reading is still the foundation, says K. C. Boyd, the 2022 School Library Journal School Librarian of the Year. Rearranging her bookshelves to be more dynamic makes the library a place where kids are continuously intrigued and drawn in by new books. The effort also drives circulation in her library.

“Literature is the priority. The print and e-book collection is the priority,” Boyd says. “The second priority is access to technology, so that kids are on an even playing field with other students from across the district and across the country. I want to make sure that the kids have clear access to materials so they can learn and discover independence, not just through a classroom assignment.”

Keeping a keen eye on the books so they’re relevant, interesting, and popular remains a top priority for all the librarians we spoke with. Even though she frequently thins out the collection, no books go to waste in Stacy Nockowitz’s middle school library in Columbus, Ohio. Everything that’s weeded out is offered to students as part of a book giveaway. This year’s giveaway was supposed to last a week—but supplies only lasted two days because kids “just went crazy for the books,” she says. “There was a lot of talk a number of years ago about ‘Are libraries going to go bookless? Are they going to go all digital?’ That kind of thing. We made a very conscious decision not to do that. It was not something that we ever even considered because our kids love having physical books in their hands.”