How to Be a ‘Poverty-Disrupting Educator’

Over 12 million American kids live in poverty. What role can schools play in disrupting its pernicious effects?

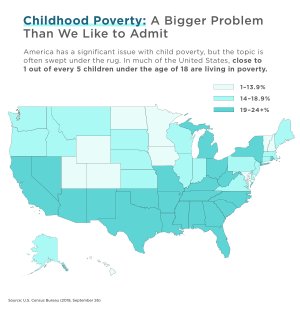

Of the approximately 73 million children living in the United States today, over 12 million live in poverty. That’s 17 percent, or around one out of every six kids. Statistically speaking, there’s a high probability that some of the children who walk the halls of your school or sit in the seats of your classroom are experiencing significant economic hardship.

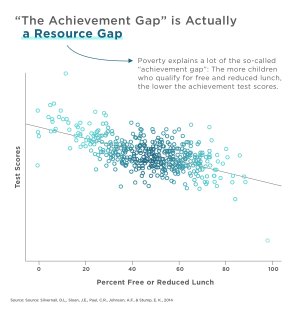

Poverty yanks kids off the track: Studies suggest that it places children in a prolonged state of catch-up when it comes to foundational skills like literacy and language development, chasing after their more affluent peers. They may have limited or no access to basic human necessities like food and clean water, fixed housing, hygiene, and consistent uninterrupted sleep—conditions that impact their physical and cognitive development and abilities, their mental health, and their internal motivation to succeed in school.

“Many of us grew up hearing admonitions from parents that we should clean our plates ‘because there are children starving in India’ (or China or Africa),” William Parrett and Kathleen Budge write in their book Turning High-Poverty Schools into High-Performing Schools, 2nd Ed. “It was not clear how eating everything on our plates would help hungry children, but what was clear was that hunger was a terrible thing that happened to other people in faraway places.”

But, as Parrett and Budge illustrate in their book, neither hunger nor poverty plagues only people in faraway places. The authors, who are professors emeritus at Boise State University, synthesized their findings from research and close observation inside of 12 high-performing, high-poverty schools—in American cities such as Brownsville, Texas, and Murtaugh, Idaho—into a case study of practices, policies, and mindsets that change student outcomes.

Despite the difficulties of the challenge, they remain resolutely optimistic, maintaining that “any high-poverty school can become a high-performing school.”

I sat down with Parrett and Budge to discuss systemic classism and societal stereotypes about poverty, what they mean by “poverty-disrupting educators,” and why so much of their work begins with confronting mindsets.

Paige Tutt: In the second edition of your book Turning High-Poverty Schools into High-Performing Schools, you mention an educator’s “mental map”—“the images, assumptions, and personal perspectives that we hold about people, institutions, and the world in general (Argyris & Schön, 1974), formed by our lived experiences.” Why should we examine our mental maps about poverty?

William Parrett: For 15 years, we’ve been asking educators the same question: “What do people in this country believe about people who live in poverty?” Ninety-eight percent of the time, what’s the first thing they say? “They’re lazy.”

If we’re not just tolerating, but actually educating, all kids in this country, what do we have to do to be successful at that? If we have mindsets and misconceptions about people that live in poverty, how are we going to look at those kids when they come in our door?

Kathleen Budge: Often, on a phone call with somebody who wants us to come work with them—it could be a superintendent or a principal—they will say they’re worried about people’s mindsets. They’ll say: The teachers don’t think the kids can learn, they have low expectations of the kids, they blame the kids—all of these things.

Nobody at any school we’ve studied said to us, “To address these mindsets, we spent one or two years really engaged in a deep study of systemic classism in the United States.” What they did instead was get to know the students and their families very well, and developed much more grace, compassion, and empathy around what the families were facing.

Tutt: Is this related to what you call “an inquiry stance”?

Parrett: Yes. Many schools want to figure out poverty. They want a simple answer, an approach, a program, and then they’ll be there. But the high-performing, high-poverty schools know it’s a journey, and you have to do the work if your kids are going to succeed.

Budge: Right. Educators who ask lots of open-ended questions and make deep connections with students’ families through things like home visits; that decide they’re going to really focus on literacy, and then see growth in what kids achieve academically; that engage in some kind of professional development with an aim of really trying to understand poverty—that combination of focusing on relationships, experiencing academic success, and investing in professional development puts people in a time and place to examine their mental maps, to surface and think about their biases and ultimately challenge them.

Under those conditions, an educator’s mental map about what they are capable of as teachers—and what their students are capable of as learners—fundamentally changes. The work dispels some of the stereotypes that they are likely carrying around in their minds.

Eventually, poverty-disrupting educators grow into self-efficacy and act from a conviction that they can influence how well students learn, even those who appear to be unmotivated. They know their content well, understand and can apply theories about human learning and motivation, use research-based practices effectively, and engage in reflective practice.

Tutt: You suggest that high-poverty schools should ask questions about the community they serve more broadly: What has happened in the community that has shaped collective experience? Who are the “haves” and “have-nots”? What do families believe is the purpose of the school?

Why is it important to understand things at a community level?

Budge: These questions increase educators’ awareness of both the historic and contemporary marginalization of people who live in poverty. They also help them become more conscious of the ways in which power and privilege has operated, and continues to operate, in the local context, including the way in which their own power and privilege plays out. Educators who lack that context are likely to be less effective—or even harmful—because their perspectives aren’t grounded in the inequities experienced by the community or the local schools, so they may not be responsive to the assets and strengths found in both.

When these questions are asked, we have seen systems, structures, and pedagogies change at the classroom, school, district, and community levels.

At the district and community level, for example, we’ve witnessed changes in systems and policies that ensure state-of-the-art schools are built in low-income neighborhoods, and funding is differentiated for schools based on need. Partnerships with community organizations have been developed to address the interests and needs of low-income students and their families: mentoring programs, scholarship programs, community schools, food banks, medical clinics, and before- and after-school programs.

Tutt: What about the questions educators ask about the school itself and the students they serve?

Parrett: Asking the right questions in the school starts with knowing your kids first. We often ask the educators we work with: Do you know how many kids in this building have a caring, meaningful relationship with an adult? The common response is often “How would you know that?” But you can know that by getting the adults in the building together and going through the kids one by one. What do you know about each child? Can you name a teacher or staff member the student has a relationship with? And then, can we share that information and lean on each other to help reach the kids who are vulnerable or alone?

You’ve got to be really curious about the kids that aren’t succeeding, as well as the kids that are. If you want kids in high-poverty schools to attend college, for example, ask yourself why they can’t go. The college placement exams are requirements—who’s going to pay that $110 for the ACT exam? That was a huge equity issue that had to be uncovered. Now a lot of districts pay for this, as well as for kids to take AP classes. We would say that is broadening your understanding of—and becoming more aware of—the impact of poverty on kids.

Tutt: Both of your books talk about this notion of poverty disruption. What does it mean to be a poverty-disrupting educator?

Budge: There are two overarching attributes of a poverty-disrupting educator.

Stephen Covey has this great piece in his book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People about being proactive as opposed to a reactive person, being “response-able.” It’s a play on the word responsible. Poverty-disrupting educators take “response-ability” for themselves. They are able to choose their responses and refrain from blaming conditions, circumstances, or other people. They view their professional learning not only as a cognitive exercise, but also as an “identity-shaping” endeavor that is not just about “acquiring skills and information” but also about “becoming a certain person.” This entails knowing as much as you can about your own mental model related to poverty and people who live in poverty. You have to understand the work starts with you—and you have to be willing to do this tough work, to surface implicit bias, and to question your assumptions when you fail.

Tutt: Does the role of poverty disruptor differ depending on your role in a school’s ecosystem?

Budge: Absolutely. A key difference between a teacher’s and a principal’s ability to disrupt poverty is the principal’s broader sphere of influence. A principal has the authority to say, “We’re going to change the way we do business here, because it isn’t working.” That authority—informal and formal—has a really powerful effect over whether teachers are going to be willing to challenge the status quo in their classrooms and in the school more broadly.

Leadership can create safe environments for teachers to innovate, for them to feel they can step out and say something that is in their gut but they were scared to mention. Maybe a teacher is seeing something going on in another colleague’s classroom that they know isn’t really good for kids, but there’s a culture of “I stay in my classroom and I don’t advocate outside it.” That’s changing because of the equity-oriented, social justice–oriented work that’s happening in schools, but it’s still really hard for teachers to do if the principal isn’t on board.

We rarely see a school where the teachers will challenge the status quo without having the principal absolutely insisting that the status quo’s not working well for all kids. That is a key piece.

Tutt: In your book, you write that “once excellent teachers and staff are hired, the challenge then becomes retaining them,” especially because the challenges in high-poverty schools are often greater than in more affluent ones. How can administrators invest in approaches to avoid staff burnout?

Parrett: When a teacher knows their time is being valued and knows they’ve got a group of encouraging peers around them and a leader that supports them and has a relationship with them, they’ll feel a whole lot differently about staying in that school and doing this work.

But this all starts with good, competent hiring—getting the very best people you can. The typical sequence of hiring is at the end of the school year when teachers are worn out, burned out, tired, they leave and the principal handles filling those positions. If you think about one teacher affecting how many kids over how many years, it doesn’t take a lot of math to understand the importance of getting a good, promising teacher.

Then you have to actively support them; use the resources around you in your school to encourage and develop relationships among your staff. We know from talking to educators in so many of these high-performing, high-poverty schools that they don’t have high turnover. In fact, teachers actively seek to get hired into these schools. The staff work hard together and they get better together.

Budge: The most successful schools hire for fit and mission orientation. They might have prospective hires come and actually spend time in the school and observe candidates in that environment. They might even ask them to teach, or have kids conduct interviews of the prospective teacher and provide input to the principal or the hiring team.

Tutt: The work is challenging and the conditions can be stressful—what are some ways you’ve seen schools make this work more sustainable?

Parrett: Burnout was a looming concern. In a few of the 12 schools we studied, we observed programs that provide counseling for educators, wellness programs, mindfulness training, accountability support partners, and many other supports.

One of the districts that we work with, they’ve set a policy that after six o'clock at night on weekdays, all nonessential communication stops. And the same is true from six o’clock Friday night until six o’clock Sunday night. So unless it’s an emergency, administrators tell staff, “we don’t want you to be sending or receiving emails. Admin won’t be calling you. We’re going to respect your time away from school—ensure you take time to rest, to recover, to do whatever you need to do. We know it’s hard work, and when you’re here, we want you on it.”

Tutt: Whose problem is poverty? Is it a broader societal issue or something that schools can have a considerable impact on? Is it both?

Budge: We don’t bother arguing the chicken-and-egg question. A lot of scholars do: “Society has to improve before schools can” versus “No, schools have to improve before society can.” We tend to start with something that another scholar, Paul Gorski, said: “Are you taking care of your own house first?” What is it that you can do within your sphere of influence?

There is a ton that schools can do if they are willing to challenge the status quo, to challenge the system. Schools make a huge difference in the lives of kids, and those kids can break the cycle of poverty. So schools do have a role, even amidst this larger, broader societal piece that really does also need to change.

The questions we would ask educators are the questions we ask in the book: What have you done in your sphere of influence? What can you do within those parameters—and have you actually done those things?