Grace Lin on Giving Young Readers a ‘Sense of Home’

The award-winning children’s book author on stories that are like friends you can turn to—and the importance of featuring characters who ‘share a common thread of humanity.’

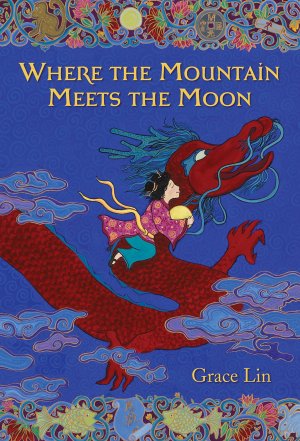

Lunar New Year is a busy time for Grace Lin, the celebrated author and illustrator of beloved children’s books like A Big Mooncake for Little Star and Where the Mountain Meets the Moon. In the months leading up to the celebration, requests pour in from schools asking for readings and art project demos—perhaps a tutorial on how to draw a Chinese dragon or the year’s lunar animal.

This surge in interest is a delight, but it also concerns Lin—a Caldecott and Newbery award recipient, and winner of this year’s prestigious Children’s Literature Legacy Award in recognition of her “significant and lasting contribution to literature for children.”

“My biggest fear is that, after I’m gone and Lunar New Year is over, [students] never see another book with an Asian person in it again. That Asians only exist at Lunar New Year, and Black people only exist during Black History Month,” Lin says. “That’s not how I want these books to be shared. Yes, share my books on Lunar New Year. But remember, I am Asian every day of my life. And your Asian students are Asian every day of their lives.”

Her cast of fictional characters—endearing, striving, eager to be understood—are reflections of their creator’s concerns, and their stories are an effort to reframe a marginalizing, and often hostile, narrative: “The anti-Asian story of hate has been told for a very long time,” Lin declared in an introduction to a virtual exhibit she curated recently for the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. “For those who believe in equality, justice, and kindness, we need to combat those stories.” One way to do this, she continued, is by replacing stories of Asians “as perpetual foreigners with real stories of Asians who share our common thread of humanity.”

I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Lin about the formative experiences that shape her storytelling, the urgency of teaching diverse books all year long, and why earnestness should make a comeback.

Emily Kaplan: Your books stand out not just because they’re beautiful, but also because they portray Asian and Asian American characters with such sensitivity and charm. Can you explain where the inspiration came from?

Grace Lin: I grew up in upstate New York, one of the very, very few minority families in the area at the time. I remember being in kindergarten and looking around the room and realizing that I was the only Asian. I thought to myself, ‘OK, I’ll just pretend that I’m not Asian. I’ll just pretend that I look like everyone else.’ And so I did.

Back then, almost nothing in the media showed people of color, so I didn’t want to be Asian. I was reading all these books with all these incredible imaginary creatures, but I would never see anyone that looked like me. Even in fantasy books where the impossible could happen, I still didn’t exist.

That made me feel ashamed: I refused to learn Chinese, I curled my hair, I did all these things trying not to be Asian. And it took me into adulthood to finally accept and embrace my heritage, which is why I create the books I do now.

Kaplan: There’s an important connection here, I suspect, to how you think about the purpose of books in kids’ lives, and yours.

Lin: So writing these books helped me claim my heritage, and I’m hoping that what I write helps kids who look like me, too. Books are like mirrors: They can show readers parts of themselves. That’s where the self-worth comes from—because when you see yourself, you have a sense of your own value, even a sense that you can be a hero, too.

The idea of books as windows is important, too. They plant the seeds of empathy and can make cultures universal, helping you understand how people who may not be like you feel in various situations. An important part of this is that if you never see any heroes who look different than you do, then you don’t believe that people who look different than you have a story worth telling—or a story worth hearing.

Kaplan: I know you visited so many classrooms, and met so many teachers and students, and I’m wondering if there are particular literacy environments or approaches that you just love to see?

Lin: I love the idea of implementing these diverse books into everyday reading and using them not just to teach the history of China, for instance, or Chinese myths—or even just literature. Show kids that we’re not reading these books just because they’re diverse but because they’re perfect for our math unit, or our science unit. There are so many studies that show that marginalized kids rarely see themselves as math thinkers, for example. So reading books that feature math, showing that a black girl can do math, is really important.

Kaplan: I’ve noticed that many of your characters—Little Star in A Big Mooncake for Little Star, and Minli in Where the Mountain Meets the Moon, for example—are these really spunky, independent-minded girls. Is that an accurate characterization?

Lin: It’s funny that you think they’re spunky—that’s not a word I would have used to describe them. I think they tend to be pretty earnest. I think “earnest” is a word that has been kind of vilified over the years. People make fun of it—it’s dorky. But I want to reclaim the word, because I think earnestness is something to be valued.

As a society, I think we glorify terrible people and I just don’t like that. I understand that they’re fascinating and it’s fun, but for me, I always felt like I wanted a hero. Not someone with the strongest muscles, but someone just trying their best. So, if anything, that’s what I would say my characters are.

Kaplan: And where do your characters come from?

Lin: So many of my characters are either iterations of myself—like Minli from Where the Mountain Meets the Moon is—or they’re more like the girl I wish I was. I have two sisters and I also have a daughter, so my life is filled with Asian American girls.

I actually feel a little guilty about that, because I do think there’s a dearth of Asian American boys in children’s literature right now. It’s a hard thing, because I want to include them more, but I also have to write from an authentic place—and my authentic place is so obviously female because of how my life is shaped so far.

Kaplan: You’ve said that literature is a powerful way to get kids to think more deeply. Can you tell me more?

Lin: I think as wonderful and fun as TV and movies are, everything is almost spoon-fed to you. How many times have we watched a TV show and completely spaced out? Literature, more than any other medium, asks you to add yourself in as you consume it.

You can’t really space out when you are involved in a book. When you read, you have to add your own imagination—and when you do that, you can’t help but get more personally involved. And the truth is, people care about things that they invest in, and when you read books, you are just that much more invested. Books are a bigger payoff.

Kaplan: You are both an illustrator and a writer—and words and pictures seem to play different roles in your books. What do you see as the relationship between the two?

Lin: I feel like with each book format, I want the pictures to have a different responsibility.

For example, in picture books like A Big Mooncake for Little Star, I want the pictures to tell a second story. So I have one story in the words, and I want the pictures to tell another.

In early readers like the Ling and Ting books, I try really hard to stick very close to words, because the illustrations are there to aid the readers in their reading. I don’t want to put extra story lines in there that might confuse the reader who’s trying to learn how to read.

Then for my novels, especially Where the Mountain Meets the Moon and Starry River of the Sky, the illustrations’ purpose is more to give ambience. They give just a visual taste of what I’m trying to create in their minds with words. Hopefully they’re creating it themselves in their imaginations, but it’s a little taste of “This is how I see it.”

Kaplan: You’ve spoken before about what you got from books as a child. What do you hope your young readers will get from your books?

Lin: I’m often asked if I’ll ever write an adult book. My answer is probably not. The children’s books that I read as a kid became part of my soul, part of my spirit. I can’t say that I feel that way about any adult books that I’ve read.

I want to create books that become part of a person, books that are like a friend that you can turn to anytime. I hope that when kids read my books, they feel a sense of acceptance and belonging. And that my books give them a sense of home. Because that’s what my favorite books did for me when I was young.