The Dual Immersion Solution

Instead of seeing English language learners as a costly challenge, districts are increasingly recognizing the assets they bring to their schools.

“Traigan sus bocas, que vamos a cantar,” croons the man’s voice—bring your mouths, we’re going to sing. The kindergartners here at Bethesda Elementary willingly oblige. As the song plays in Spanish, they bring their ears to listen, hands to clap, and bodies to dance. But at the end of the day, the song is really about those mouths.

Attending one of Bethesda’s 10 dual-language immersion classrooms, these kindergartners spend half of each day learning English language arts and social studies in English, and the other half learning math, science, and Spanish language arts in Spanish. At the school, more than half—57 percent—of students are non-native English speakers, or English language learners (ELLs), and 9 in 10 students are low income.

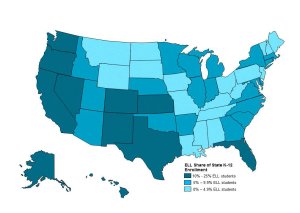

Bethesda is among a growing number of Gwinnett County Public Schools (GCPS) in Georgia offering such an opportunity. These schools aren’t alone. Driven by rapidly increasing linguistic diversity in public schools, districts throughout the country are scrambling for ways to meet the needs of ELLs, who now total nearly 5 million U.S. students—an increase of over 1 million since 2000.

But instead of seeing ELLs as a costly challenge—requiring remedial support or additional staffing, for example—many districts, like Gwinnett, are acknowledging the assets these students bring to school, and in response have created dual-language immersion programs where English learners and native English speakers learn together. Utah and Delaware have recently launched statewide dual language initiatives, as have larger urban communities in New York City and Portland, Oregon, and smaller cities like Elgin, Illinois, and Kalamazoo, Michigan.

A number of these programs are already reporting academic and social gains from participating students, findings that build on a growing body of research that shows dual immersion offers academic and social benefits for English learners and fluent English speakers. A study of Portland’s program, for example, found that students enrolled in dual-language immersion programs had much better English reading scores than peers in English-only programs. And at Bethesda, the school’s academic growth is higher than 91 percent of schools in Georgia, and the percentages of students scoring proficient or better on standardized math, science, and social studies tests are above state averages.

“The world that students are going to live in is going to require a large number of individuals who are able to navigate linguistic and cultural borders,” says Jon Valentine, GCPS’s director of foreign languages. “Fundamentally, we want Gwinnett students to be at an advantage globally.”

Changing Population, Changing District

Gwinnett County covers 437 square miles of the Atlanta metro region, encompassing walkable suburbs, miles of strip-mall-laden parkways, and even some farmland. In the past three decades, the county has grown dramatically, shifting from a largely white and English-speaking population of 167,000 in 1980 to its current mix of 1 million residents, 230,000 of whom are foreign-born.

The county’s diversity is readily visible from the road, as parks and cookie-cutter two-story homes are interspersed with pupuserías, churches with signs in Korean, and shops promising to buy your gold. Within GCPS, students and their families speak well over 100 languages, and over 20,000 of the district’s 176,000 students are formally classified as English language learners.

Intrigued by the research showing that dual immersion programs can sharpen student focus and boost working memory and reading comprehension, GCPS began offering dual-language programs in Spanish at three elementary schools in 2014. Now, four years later, it offers seven programs in Spanish and one in French, and will launch a Korean program in the fall of 2019 (partly in response to interest from the county’s growing population of Korean speakers). Families apply for spots in the programs, with preference given to those who live near the school. Demand is rising faster than the programs are growing—nearly all of them have waiting lists.

“A lot of parents are more involved now thanks to the dual-language immersion programs,” says Marie Bouteillon, a former teacher who founded several dual-language immersion programs in New York City and now works with GCPS.

Some of appeal comes from studies showing that “two-way” dual immersion programs like Gwinnett’s—with roughly equal numbers of native speakers of each language—can be a more effective way to advance educational equity for students over pull-out or one-way programs that keep students segregated by language ability, or full immersion programs where students speak only English. In two-way programs, English-dominant and English-learning students learn side-by-side, taking advantage of their complementary strengths and weaknesses, with each getting a turn to serve as the expert and the learner.

Research has found the benefits are twofold. The instruction can be one of the most effective ways for English learners to develop their language and academic skills, but it also helps native English speakers and English learners improve their communication skills, empathy, and cultural awareness—not to mention giving them an advantage in the job market. One study even suggests that bilingual instruction may forestall the onset of Alzheimer’s disease later in life, presumably by making the brain work harder as it processes information in two languages.

Getting Buy-In

Down the hall at Bethesda Elementary, a first-grade classroom is full of cheerful chatter, as the roughly two dozen students search for the vocabulary to describe the color of objects in Spanish. Their teacher walks them through a poster with sentence frames—written examples of common conversational phrases—to get them started. When she asks them to turn and talk to their partners, the pairs scan the board, checking their vocabulary against the frames.

While dual immersion programs are rising in popularity, credentialed bilingual teachers like those at Bethesda are hard to come by. States regularly report shortages of bilingual teachers (pdf), and districts exploring dual-language immersion often complain of similar shortfalls.

As a result, many school districts rely on visiting teachers from overseas to staff the non-English instructional portion of dual-language immersion programs, yet these teachers generally have little experience working in U.S. public education, and their training may not align well with expectations in American schools. Further, since visiting teachers usually cannot work in the United States for more than five years, this approach to staffing bakes high teacher turnover into the district’s future.

At GCPS, the district has been able to avoid some of these headaches through a combination of luck and persistence. The district had teachers on staff who were already fluent in Spanish and French and has even found some teachers who know Korean. But it has also launched significant recruitment efforts at local universities, and even high schools, to get more bilingual teachers in the district.

But building a multilingual teaching force is just one complication of implementing a dual-language immersion program. Longevity for GCPS’s dual-language immersion programs also requires sufficient, sustained family demand, and the benefits aren’t always apparent to families—both native English and non-native English speakers.

When GCPS’s Baldwin Elementary prepared to start its dual immersion program in 2016, Assistant Principal Gregory Jackson said that there was “fear and anxiety,” surprisingly, among some native Spanish-speaking families who worried their children wouldn’t become proficient in English if they spoke Spanish at school. And while many English-dominant families see bilingualism as a potential asset, some have been more suspicious. Local conservative activists, for example, have protested GCPS’s efforts to make the district more welcoming to English language learners and children of immigrants.

In response to these concerns, the district has hosted community meetings touting the benefits of learning another language, emphasizing that “the power of learning another language builds a better person and increases your opportunities in the workforce, your mindset, and your experiences as a human being,” says Jackson. The publicity is already getting easier, say staff, as the families of enrolled students are starting to spread the word themselves.

The National Narrative

The conversations over the benefits and drawbacks of dual immersion aren’t just happening in Gwinnett County, though. Searing national debates over how American culture, history, and identity intersect with controversial questions about language and immigration have only increased in recent years.

At the same time, more schools than ever are looking for ways to expand access to multilingual learning opportunities for students, with some districts, like San Antonio and Grand Rapids, Michigan, finding that dual immersion may attract new families or turn around schools. A survey of states by the U.S. Department of Education found that the majority reported that their districts offered at least one dual-language program in the 2012–13 school year. While Spanish and Chinese were the most popular languages, a total of 30 languages were offered.

Our school is probably a good representation of what the world’s gonna be as these kids get older—we are a huge melting pot.

More recently, California has launched a statewide effort to expand access to dual-language programming, driven by a voter-approved ballot measure. There’s even a national effort underway to get more states and districts to adopt the Seal of Biliteracy, a credential displayed on transcripts and diplomas that recognizes high school graduates who are proficient in two or more languages; 34 states have already adopted the seal.

And in Gwinnett County, the successes of dual immersion programs like Bethesda’s have left district leaders hopeful they can offer more students the opportunity to be multilingual.

“Our school is probably a good representation of what the world’s gonna be as these kids get older—we are a huge melting pot,” said Courtney Mitchell, a Bethesda Elementary speech language pathologist, PTA leader, and mother of a fourth grader at the school. “I love that my daughter’s here, so that she won’t just be stuck with one population or one culture. She’s getting to see everyone.”

But for now, Bethesda’s kindergartners don’t seem too concerned with the politics of immersion. They’re here to learn—in both Spanish and English. The song ends and they line up and file out of the classroom. As they go, most absentmindedly paw a sign taped to the door, where there’s a picture of a big jar reading “Galletas Intelligentes”—Smart Cookies.