Cross-Training: Arts and Academics Are Inseparable

At one Boston school, students major in theater, dance, instrumental music, vocal music, or visual art.

At the Boston Arts Academy, however, there's nothing dispensable about singing -- or dancing, acting, drawing, and painting. The arts at this public school are central to the mission of educating students in math, science, and the humanities.

What could singing lessons possibly have to do with science class? As teachers here see it, tough training in the arts is training for everything important, and it's a kind of preparation teenagers passionately want and need.

"There's a deep-seated belief here that art allows young people to develop a creative and entrepreneurial understanding of the world," says headmaster Linda Nathan, who helped found the school. "In arts, kids learn there's not just one right answer. They learn that judgment counts. They learn to connect."

Using a carefully calibrated mix of rigorous high school academics and classical arts training, this seven-year-old academy aims to help 415 teens become capable, creative men and women -- artists and scholars with a faculty for self-reflection and the drive to continually refine their work. Students, many of whom enter ninth grade with no prior artistic training, choose a major from among theater, dance, instrumental music, vocal music, and visual art. Arts and academics are not separate endeavors here; they are deeply connected disciplines, and teachers draw on the rigors of one to feed another.

The results are impressive. The academy's students, many from low-income families and drug-impacted neighborhoods, produce exceptional art for their age -- and 97 percent of them go on to college. Though it's an arts school, academic achievement is a priority: According to the most recent available data, 92 percent of the academy's sophomores passed the state's English test and 80 percent passed math, compared to 73 percent and 67 percent of Boston students overall.

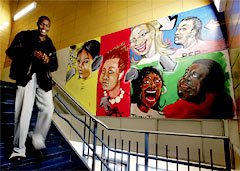

The Boston Arts Academy shares a generic four-story building with Fenway High School, directly across the street from Fenway Park, home of the Boston Red Sox. Visit on a typical morning, and you'll hear young voices singing scales in the practice rooms, while the rumble of hand drums emanates from a distant classroom. In the dance studio, you'll see Artistic Dean Fernadina Chan urging freshman dancers into deeper stretches as an interpreter signs her instructions to a petite hearing-impaired girl in the front row. If you see pairs of teens shouting and shoving each other in the hallway, don't intervene -- they're acting. Moments later, they'll break into laughter and discuss what went right in their scene and what went wrong.

As a pilot school within the Boston Public Schools, the academy has the autonomy to determine its own spending priorities, policies, and curriculum. In exchange, it strives to be a national beacon for artistic and academic innovation. Teachers meet this mandate by linking academic subjects with the arts: The math curriculum, for example, incorporates principles of design, and science teachers use musical instruments to study sound and stage lighting to demonstrate the properties of light.

Yet there's something more profound about the academy's artist-scholar concept than just meshing subject matter. The message educators here give students is that just as you strive for excellence in art, you must try your best in everything you do. Humanities teacher Anne Clark explains it this way: "For at least half the school day, students feel successful. If a student is struggling, I can go down the hall to his or her arts block and see them being a genius. The trick is to use that artistic passion and power to get them through their academics."

One of Clark's students showed the potency of this approach last spring when Clark reviewed the teachings of Aristotle with her senior humanities class. Aristotle believed people must constantly strive to perfect themselves, Clark said; in the philosopher's eyes, "art could make you more perfect. In fact, the purpose of art is to inspire you in becoming."

Theater major Michael Cognata made the connection between this lesson and his life: "The things we learn in theater could be good for theater, but they're also good for other areas of life."

"Like what?" Clark asked.

"Like becoming a responsible man."

Cognata had to be responsible to handle the academy's workload. At one point last spring, he was rehearsing for three shows while completing his senior requirements, which included a fifteen- to twenty-page paper and a forty-five-minute presentation on historical periods and their respective art forms. He said then, "Pretty much, I go from rehearsal to rehearsal to rehearsal to bed to school to rehearsal."

During Cognata's senior year, he and a half-dozen other theater majors performed in A More Perfect Union, by playwright Kirsten Greenidge, with the professional Boston theater group Company One. Audience members at the play -- which tackled such fierce issues as racism, immigration, and sex trafficking -- had to check the program to discern which actors were students. The same year, the school's Charlie Brown Blues Band played two shows to packed houses at the popular Cambridge, Massachusetts, venue the Ryles Jazz Club. Last summer, a team of academy teachers and students, including Cognata, was asked to perform at Scotland's Edinburgh Theatre Festival. Feats such as these underscore the professionalism the academy demands of its students in both their arts and their studies. At the end of the year, each student must present a portfolio of work to a panel of teachers to demonstrate how he or she has grown.

The panelists, many of them practicing artists, don't cushion their critiques.

"I'd never acted before," says junior Jesse Tolbert. "It's kind of scary to be like, 'Use everything we've taught you in the past two years and make the best scene or the best monologue. OK? Go.'" If the panel is critical, he says, "you feel terrible, but that's a thing about life, growing up. You have to deal with not being your best."

Lee Beard, who was a senior visual-art major last year, says, "You come to this school saying, 'I want to be an artist,' and you think it's going to be one thing, and you end up making art galleries, building portfolios, learning your strengths."

Tolbert has his own critique of the Boston Arts Academy. Compared to Josiah Quincy Upper School, the rigorous pilot school he attended, he finds the academic classes here less challenging. But he says the academy is a more diverse and cohesive community, and he'd rather be here than at any other school in Boston.

The academy doesn't handpick incoming students for their prior superstardom; admissions are academic blind. Of the 704 applications the academy received for this fall, it admitted 130 students based on artistic potential and demonstrated commitment alone. Sometimes this system yields situations such as the one last year in which eight of the twenty-two freshman visual-art majors qualified as having special needs.

Given the wide-ranging skills of entering students, the entire faculty -- humanities teachers and dance teachers alike -- emphasizes literacy and is trained on it. Headmaster Linda Nathan reasons that if students can't read well, they can't do math well, and if they struggle with math, they'll struggle in music.

Teachers and staff support students by fostering close relationships and maintaining the resources to fully include teens with special needs (such as the hearing-impaired dancer in Fernadina Chan's class) in regular classes. Students meet four times a week in groups of eight to ten students with the same adviser for all four years, and the staff provides one-on-one counseling and support groups for issues such as coping with family stress and chronic mental health problems. The Boston Arts Academy is the kind of place where students have their teachers' home phone numbers, and where music teacher Allyssa Jones's graduation gift to one student she had grown especially close with was the piano on which she herself had learned to play.

If you think the Boston Arts Academy couldn't possibly get by without its own fundraising team to provide all these opportunities and resources, you're right. The Boston Arts Academy Foundation, with a staff of five, arranges partnerships and raises more than $1 million a year to support the school's programs. Aid also comes in many forms from the ProArts Consortium, a group of higher-education art institutions in the Boston area, which helped found the academy. The ProArts schools -- the Berklee College of Music, the Boston Architectural Center, the Boston Conservatory, Emerson College, the Massachusetts College of Art, and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston -- lend the academy their performance spaces and allow its students to take college-level classes free.

For all these investments, though, it doesn't matter to academy teachers whether alumni go on to pursue art professionally (a handful do). They want their students to go to college, period, and they want graduates to possess the skills and sense of responsibility to engage with their communities. "There is no art without an audience, and there is no democracy without people's investments," says Nathan. "We'll know we've done our work when our graduates are sitting on the boards of major and minor arts organizations."

Michael Cognata, though a bit young still for a board membership, has soaked up the academy's mission like an eager teenage sponge. He planned to enroll this fall at Boston's Wentworth Institute of Technology to study engineering. His friends don't understand why he's not pursuing theater, he says.

"I wanted to do something different," Cognata explains. "I wanted to be on the other side -- go to a show for once instead of dissecting it -- but I'll always have some connection to theater." He'll also have the discipline, leadership, and teamwork he believes theater has given him no matter what work he pursues -- it's all in the process of becoming.

Go to "How to Grow Students' Opportunities Through Private Partnerships."