Real World, San Diego: Hands-On Learning at High Tech High

Students prepare for the real world through technology-enabled projects.

Editor's note: On June 27, 2009, High Tech High biotech teacher Jay Vavra and several of his students returned to Tanzania to hold a bushmeat-identification workshop to help local wildlife-protection officials fight poaching. For more information, go to the group's Web site, High Tech High African Bushmeat Expedition, and read the expedition journal. (Watch a trailer for Students of Consequence, the students' award-winning documentary about their 2008 expedition.)

As I navigated her busy classroom with a microphone this fall, sophomore Maya Walden paused in researching the root causes of genocide to ask what I planned to do with my recordings. I explained that I would use editing software to meld the best clips into a soundtrack for an audio slide show, to appear online.

"Oh," she said. "We could probably do that for you." (And they did. Check out their work.)

The episode reflects not only the confidence and abilities of one good student but also the entire attitude of High Tech High. The San Diego charter school exists to prepare students -- all kinds of students -- to be savvy, creative, quick-thinking adults and professionals in a modern world. It has scrapped a lot of what's arbitrary and outdated about traditional schooling -- classroom design, divisions between subjects, independence (read: isolation) from the community, and assessments that only one teacher ever sees. (Watch a series of videos about High Tech High.)

Instead, the textbook-free school fosters personalized project learning with pervasive connections to the community. Any visitor can see the evidence in the students' engagement and the eye-popping projects that adorn almost every corner and wall -- many of which the teens have exhibited to local businesspeople, not just teachers. As the school's name implies, technology enables many of the projects students create. And teachers routinely craft lessons that blend subjects, reflecting how interwoven they truly are.

On all fronts, the teaching and learning experience here is keenly attuned to the demands of today's world, not the industrial world that existed a hundred years ago when the American school model came into being.

"How many teachers have heard those questions: 'Why are we learning this?' 'What does this have to do with what I want to do in my future or my life?'" says Spencer Pforsich, Walden's humanities teacher. "When students see the interconnectedness of the subjects they're learning, they feel it's more relevant, more meaningful, and more authentic than if they're working in isolation."

A coalition of San Diego business leaders and educators, led by former Qualcomm executive Gary Jacobs, launched High Tech High in 2000. The institution has expanded from a single school with 200 students to a network of eight schools spanning grades K-12 and serving 2,500 students. It has become a school-development organization trying to grow the number of schools built on the same model, and its connection to local businesses has remained a defining feature. Admission is via random lottery. So far, 99 percent of graduates from all the campuses have entered college.

At the original campus, the Gary & Jerri-Ann Jacobs High Tech High, housed in a former U.S. Navy training center near the San Diego airport, the building itself invites inquiry. Most classrooms are glassed-in pods within a single open space, a design that makes all the classrooms and common spaces feel connected while still providing a quiet space for work. The transparency is no accident; administrators here value teacher learning as highly as student learning -- so highly, in fact, that High Tech High has started its own graduate school of education -- and they want students to see that. The 35-foot ceilings and the skylights and exposed metal beams make the space industrial yet inviting, a combination that evokes a sense of people and machines working in harmony.

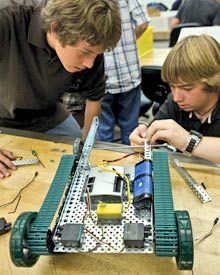

Projects form the core of the learning experience at High Tech High. In some classes, like Jay Vavra's junior biology course on conservation forensics using DNA barcoding, a full five-week period consists of a single project. In many cases, community members participate as experts, clients, or final judges. Teachers try to design the projects to mesh multiple subject areas, allow students the flexibility to choose their own focus and approach and, ideally, serve a useful purpose beyond schoolwork.

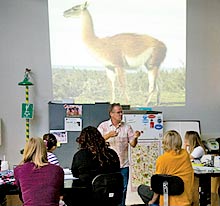

In Vavra's class this fall, pairs of students were making observations about meat samples in test tubes and preparing to isolate the DNA to identify which meat was which. (Construction of Vavra's lab was underwritten by Biocom, a consortium of southern California life sciences companies.) Once the teens learned the procedure called crude cell extraction, says Vavra, who holds a PhD in marine biology, their project would be to find ways to do it more cheaply and efficiently. Ultimately, conservationists will use the improved procedure in African street markets to identify meat from illegally poached animals.

"Oh, that's strong!" says J.V. Hill, a junior with a black buzz cut, sniffing one especially pungent sample. "We have to write that down."

The kids seem nonchalant about the lofty purpose of their work; this is just a regular day in class. But compared to the textbook-heavy work their friends in other schools do, they feel they have the much better deal. "The hands-on experience of being able to do it instead of just reading about it -- it's exciting to know that you're actually doing something to help an issue in the world," Hill says. "I like feeling that."

Down the hall, students in Jeff Robin and Blair Hatch's team-taught art and biology/multimedia (yes, biology/multimedia) class work at computers designing informational DVDs about blood-related health issues. By semester's end, the teens plan to incorporate the DVDs (played on laptops) into art pieces that would appear at a local gallery and potentially be auctioned to benefit the San Diego Blood Bank. (See the class's project Web page.)

That same day, David Berggren's Engineering Design and Development students are off campus meeting with community groups for whom they will spend the semester designing a customized tool. One student team plans to make dog-obedience signs for the San Diego Humane Society; two others working with the San Diego Oceans Foundation will build a fish pen to protect 11,500 sea bass from avian predators.

In Pforsich's humanities class, the genocide research under way by Maya Walden and her peers is a lead-up to the Waterways to Peace project. The joint effort by Pforsich and math/science teacher Andrew Lerario will require students to research the African political struggles caused by a scarcity of natural resources (such as water) and create a documentary film and a model water-purification plant. As usual, students will exhibit their final work before peers, teachers, parents, and members of the community.

High Tech High educators shore up this real-world connection with personalization, paying attention to individual students' needs and empowering them to match their projects to their passions. Juniors spend a full semester, eight hours a week, working at internships tailored to their needs and interests. Almost every adult at the school serves as an adviser to ten students, meeting at least weekly with the group and keeping each advisee for all four years. Pairs of core-subject teachers (one humanities, one science/math) share the same two classes of students so they can collaborate on cross-disciplinary projects and better support students and each other.

Frequent assessment also underpins the work done here, where even a D is considered a failing grade. Rob Riordan, a school founder who holds the self-created and slightly tongue-in-cheek title emperor of rigor, explains that at High Tech High, "assessment is an episode of learning. It's not an endpoint. It's going on one way or another just about every day." These episodes take the form of everything from quizzes to oral presentations to peer review. For the big projects, students exhibit their final product to the community.

It sounds surprising, but 98 percent of the school's funding comes from its $6,900-per-pupil allocation. An influx of start-up grants and private donations helped the original High Tech High get off the ground, but now it runs on about the same budget as a traditional school. Community partnerships help, as does the administration's tight focus on empowering teachers (an energetic bunch -- the average age across all High Tech High campuses is thirty-one). Founder and CEO Larry Rosenstock calls himself "support staff."

Art teacher Jeff Robin has seen how all this hands-on experience pays off: Some of his science-minded students have gone to work in a blood lab at a nearby hospital, where Robin's father is chief of pathology. Though they've signed on as technicians or research assistants, the teens have quickly found their coworkers calling on them for skills beyond their job descriptions, such as presentations and Web design.

"They have all these skills that nobody else in the workplace has," says Robin, "and the employers need them."