Capture the Learning: Crafting the Maker Mindset

Plan a maker education program by identifying the content and skills you want to develop, and approach it as teaching creativity via PBL and design thinking.

You've heard some good stuff about the maker movement such as how making helps students learn through embodied cognition, creates a mindset that's empowering, and builds creative confidence. You're interested in crafting some maker lessons but don't know where to start or how to do something that works in your classroom. Or perhaps you're worried that you don't have time to do a long, involved project. How do you still teach the Common Core or cover the required curriculum? These simple steps will get you started.

Teaching Creativity?

First, identify the content you need to teach. Start with a simple lesson or unit to get your feet wet. Is it atomic orbitals or the grammatical structure of Mandarin? What specific information and material should students understand deeply through the experience?

Second, think about the skills that you want students to use and practice. Do you want them to develop empathy for the characters in a novel or for abolitionists during the Civil War? You can craft a lesson that allows students to practice and hone these specific skills. To teach close observation in biology, ask students to adopt a tree for the year and visually record how it changes over time.

Third, think about restrictions or limitations for the project. All creativity needs restraints. It could be as simple as the materials you want students to use. Perhaps you limit them to using recycled materials that they gather. Have them explore the properties of the material before they use it, because you cannot assume that students have making experience. How much can wire bend before it breaks? Successful projects don't have to be high tech -- they can be as simple as paper and colored pencils.

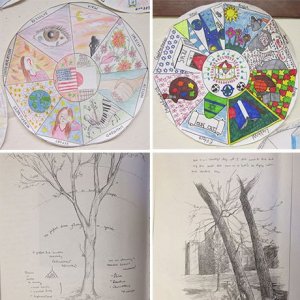

Fourth, craft a main question, the simpler the better. Ask math students to create a tool that can measure the height of a flagpole. Make it relevant. Ask world history students to make mandalas that demonstrate their understanding of the eight-fold path in Buddhism. How would you show the "right mind" or right action? For math and science students, how can you measure the water output of a stream?

The Power of Design Thinking

Capture the learning. Ask students to document and assess their process, identifying the thinking skills they've used. What was hard? Where did they get stuck? What did they do to get past it? This builds habits of mind like grit.

Grading creative projects can be difficult, so create a rubric that includes students' process. Have them tell the story of their thought process. And have them write a paragraph about their intent, as this allows those with lesser making skills to explain what they were trying to convey. Grade craftsmanship, because no matter their skill level, sloppy projects detract from the creator's intended message.

Showcase the projects. Honor your students by displaying their work. It can be a museum walk in the classroom or a gallery opening one evening, inviting parents in to celebrate.

In a maker classroom, no two projects look alike, which can be difficult to manage within a 40- or 50-minute period. Stanford’s d.school has developed design thinking, which is a codification of the artistic or scientific way of thinking:

- Understanding and empathy

- Defining the problem

- Brainstorming solutions

- Prototyping a solution

- Testing the solution

- Reiterating.

Design thinking allows teachers to have control over messy maker projects. You can set distinct time restraints for different steps of the process that will keep everyone on roughly the same timeline. For instance, you can insist that the research phase is finished by a certain date so that students can share information with one another before they move on to the brainstorming stage.

Understanding vs. Experience

So should students make things? Asking them to express an idea translated into another medium requires them to know something holistically and more deeply. They must understand both its complexities and its parts. It's the same as knowing something well enough to teach it -- you have to understand it completely, as well as how all the different pieces fit together. Students may know how many troops died during the Vietnam War, but going to the Memorial and experiencing it physically, walking through the space, touching the names and having a personal connection is a more human way of knowing. This understanding is intricately tied to our senses and creates a deeper, layered knowing of an abstract concept, making it personal and relevant.