7 Digital Tools That Help Bring History to Life

Challenging games, fun projects, and a healthy dose of AI tools round out our top picks for breathing new life into history lessons.

As Carl Sagan once said, “You have to know the past to understand the present.” But great history teachers know that doesn’t mean you need to rely on ancient teaching tools.

Fortunately, cutting-edge digital software—much of it free—can breathe new life into history lessons, allowing students to drop into historical venues, converse with long-dead presidents or kings, and inhabit eras in ways that can shift their perspective.

While it can be hard to separate the wheat from the chaff, the best digital tools are ones that “support student engagement as they make rich and meaningful connections to people from the past,” writes Matthew Farber, an associate professor of educational technology at the University of Northern Colorado.

We’ve compiled a list of seven teacher-tested tools, and we lay out how educators are using them both to enhance their lessons and to bring history closer to the present than ever.

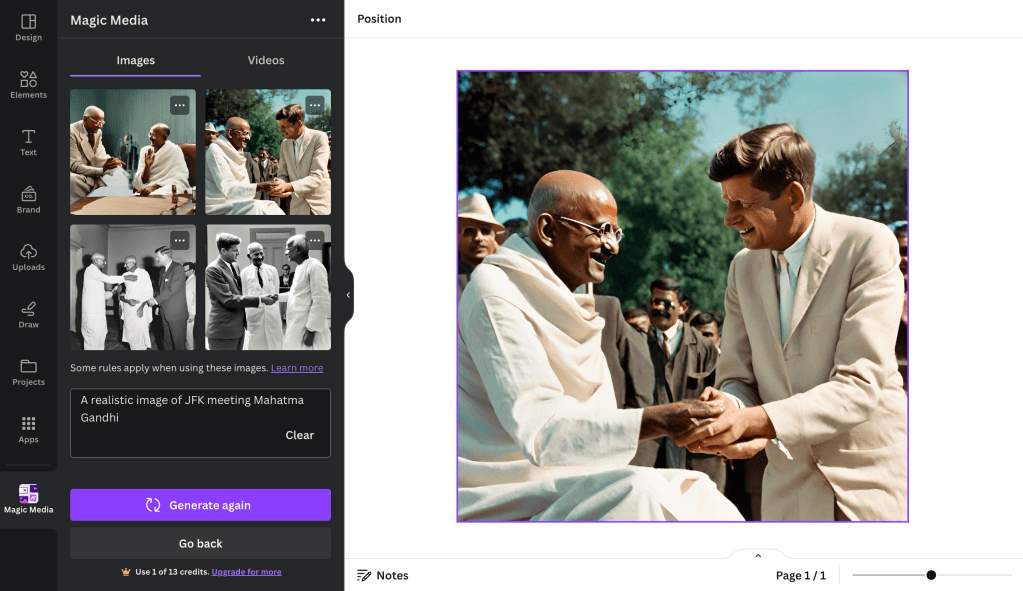

AI-generated images spice up lessons

AI image generators are fun to mess around with—but they can also help drive critical thinking in the history classroom. Teachers can use them to generate fantastical images from before the dawn of photography, explained history educator and edtech expert James Beeghley in a presentation at ISTE 2023. For his U.S. history classes, Beeghley had the AI generate photograph-style images of scenes like the signing of the Constitution and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which he then added to his class presentations. World history teachers can go even further back in time, asking the AI what it looked like when visitors flocked to the Roman Colosseum, for instance. Teachers can use free image generators from Bing, Craiyon, or Canva to produce these images, then drop them into class presentations. (We recommend specifying “photograph-style” in your prompt for maximum realism.)

Beeghley warns that AI image outputs tend to be full of inaccuracies—but that can help create an engaging lesson. After generating a fake historical image based on your current unit of study—perhaps an intentionally deceptive one, such as of two famous figures who never met—challenge students to point out all the flaws and anachronisms they can find.

iCivics offers short games about governance

iCivics—a nonprofit founded by former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor—aims to improve civics education in America through free games. And unlike many other educational websites, the games feel modern—not as if they’re from the age of dial-up internet.

Thanks to iCivics’ games, “when I taught social studies to middle school kids, I observed their engagement with content that might otherwise be boring to 12- and 13-year-olds,” writes Matthew Farber. “For instance, to help students learn about the Bill of Rights, I had them play ‘Do I Have a Right?,’ a game where players learn experientially by running a civil rights law firm.” Other games include Counties Work, where students see the ins and outs of local governance, and LawCraft, which challenges students to craft a bill and try to get it through Congress.

iCivics now has about 20 different games, each lasting from around 10 to 30 minutes. After students play the games, “the next step for the teacher is to create a great performance assessment—although iCivics provides great reflective activities to use after the game has been played,” notes social studies director Andrew Miller.

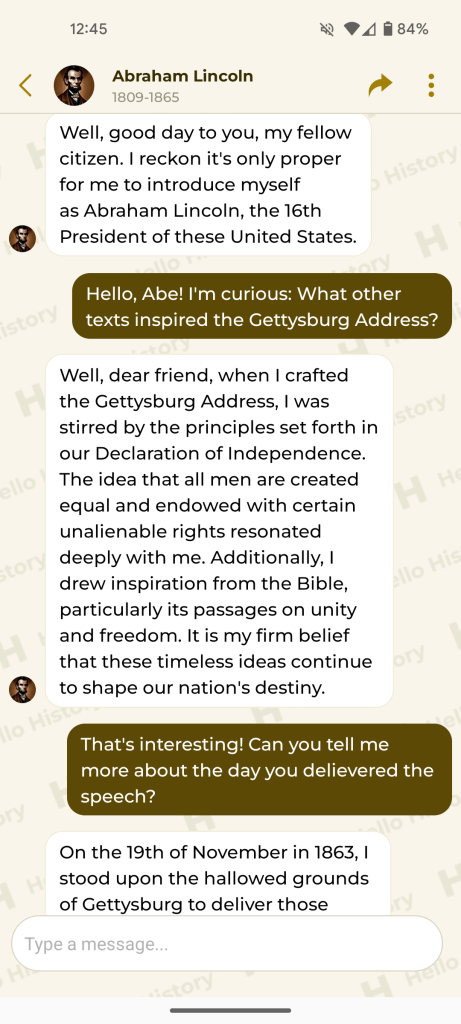

AI history chatbots are fun fodder for critical analysis

While history teachers can’t get Napoleon or Eleanor Roosevelt in class as a guest speaker, AI can help students “interact” with historical figures. In a presentation at ISTE 2023, edtech professor Maureen Yoder suggested that teachers check out Hello History—a ChatGPT-powered app that can let students carry out conversations with dozens of figures from around the world, from Cleopatra to Mahatma Gandhi.

The app is free until users hit a 20-message daily limit—so another option is to go directly to ChatGPT and prompt it, “Please roleplay as Thomas Edison for the rest of our conversation.” When we tried it, the AI did a fairly good job of staying in character—refuting the notion that he stole ideas from Nikola Tesla by saying, “In the world of invention, it is not uncommon for individuals to draw inspiration from one another’s work and build upon existing ideas.” Though it misrepresented Edison’s childhood hearing loss, suggesting it wasn’t until his elder years that he developed partial deafness.

But that, too, presents an opportunity, as the dubious quality of AI-generated information can be made part of the assignment. Before his students write biographical essays, historian and history educator Jonathan S. Jones has students closely inspect history-related output from ChatGPT to identify “factual errors and information that was missing crucial context,” then spend some time editing the AI’s output to correct the errors and inaccuracies.

Minecraft gives a hands-on understanding of ancient buildings

When ancient structures or famous buildings come up in class, students can benefit from a deeper understanding of how those structures were built. To that end, some teachers are using Minecraft—the popular game that lets players gather resources and build blocky structures out of wood, stone, and more.

In a lesson on ancient Egypt, for example, students can dive into a digital Minecraft world “in groups of two or three” and gather resources to “create structures that show where Egyptians ate and lived,” suggests Meenoo Rami, a former English teacher affiliated with Minecraft’s Mentor Program. Or, instead of a blank world, teachers can help students load up one of Minecraft Education’s prefabricated lessons. There’s one that teaches about the construction of the pyramids; another that has students reconstruct UNESCO-recognized monuments in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan; and another that has students rebuild the inside of the Titanic. Minecraft Education isn’t free (unlike the other tools on this list), but administrators can buy schoolwide subscriptions at a discount.

Google Arts & Culture’s games make art history fun

If your history class covers art movements, cultural eras, or ancient artifacts and monuments, then Google Arts & Culture is quite possibly the site you’ve been dreaming of. The free-to-use website has incredibly diverse resources: thousands of digitized works of art, 3D models of famous buildings and sculptures, and 360-degree virtual walkabouts of museums like New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Google Arts & Culture also offers a wide variety of educational games. Here are two of them:

- Odd One Out — Players must try to identify the AI-generated “imposters” hidden next to three actual artifacts or works of art. (For example, “Find the AI Generated Throne.”) Students click any of the real works of art to learn more about them. There’s also a media literacy aspect: The more kids play, the better they may get at identifying AI-generated imagery based on telltale signs like a lack of concrete detail and some fuzziness around the edges. (Still, it’s quite hard, even on your 20th try.)

- 3D Pottery — Another challenging game, this one asks players to manipulate a spinning ball of clay and re-create ancient works of pottery from around the world. Students get a hands-on understanding of this ancient art form—without the mess of real clay.

Recording podcasts turns students into historians

Podcasts are all the rage. But rather than having students listen to podcasts, some history teachers are encouraging students to produce their own.

In her ISTE presentation, Maureen Yoder proposed having small groups of students script podcasts with conversations between figures who never actually met in real life—like Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton, or Harriet Tubman and Rosa Parks. Students must decide, based on what they’ve learned, what these figures would likely say to each other. Then, members of each group can record the lines in character or input the script into text-to-speech software. Groups can edit the podcasts together using free audio editing software like Audacity.

Besides historical fiction podcasts, students can become genuine historians by recording and archiving conversations with elders in their communities. Inspired by StoryCorps, a nonprofit that aims to preserve stories from Americans of all backgrounds, Director of Technology and Innovation Kevin Brookhouser has his students prepare a list of questions and record conversations with their grandparents. “This is not just about sharing family stories; it’s the academic work of a historian, creating primary sources for future scholars as we piece together our past,” he writes. Recording is easy, Brookhouser explains; students can use their phone or tablet or a free online voice recorder on their Chromebook.

Mission US offers free games about American history

Many U.S. history teachers appreciate the story-driven games from Mission US. The games—complete with voice acting and animated cutscenes—have students play as a fictional child from a real era of American history and make difficult moral and strategic decisions. In one such game, For Crown or Colony?, “students are put in the shoes of a printer’s apprentice in 1770 Boston and encounter both Patriots and Loyalists around the time of the Boston Massacre,” writes Rebecca Rufo-Tepper, a director of digital learning and former public school teacher. “The goal is for students to choose where their loyalties lie. Along the way, they engage in empathy and explore issues of liberty, equality, and perspective.” Rufo-Tepper recommends playing the game collectively at the whiteboard, having the class discuss what choices to make, before letting students break out to play it individually.

Other games on the site include 1866, Westward Expansion: A Cheyenne Odyssey; 1907, The Immigrant Experience: City of Immigrants; and 1960, The Civil Rights Movement: No Turning Back. It’s worth noting that each game takes one to two and a half hours to finish, so they’re not feasible to complete in one sitting. However, the site does save progress with a free account, so history teachers could spread out the gameplay over multiple class periods or assign it as homework.