20 Years of Data Shows What Works for LGBTQ Students

Leaning on decades of research, the director of GLSEN’s Research Institute says schools should prioritize four key areas when supporting LGBTQ students.

Twenty years ago, students weren’t bullied or harassed in schools because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. At least, that’s what many educators said in the late ’90s when advocacy groups first began digging into the urgent problems reported by LGBTQ youth in America’s schools.

“We don’t have a problem here” and “Our school is fine” were typical responses, recalls Dr. Joseph Kosciw, director of the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN) Research Institute.

It wasn’t true. LGBTQ students were regularly subjected to verbal and physical harassment, but there was no national data about their school-based experiences, according to Kosciw. In fact, there was very little information about LGBTQ youth at all, outside of academic literature—most of which consisted of retrospective reports that were far removed from the real voices and experiences of students themselves.

“That was really what sparked the need,” says Kosciw. “There was no national evidence, and GLSEN realized we need to be able to demonstrate what’s going on across the country.”

Launched in 1999 and conducted every two years, the National School Climate Survey became the largest body of research about LGBTQ students in U.S. schools, providing a rich and detailed look into topics like school climate, ingrained cultural biases, and the indelible impact of hate speech and discrimination on children. Ultimately, the survey sketched the first tentative outlines of a formerly invisible population and tracked the well-being of LGBTQ students and the schools that educate them over the next two decades. It delivered a complex portrait that’s both cause for optimism—school-based supports do have a positive impact, for example—and a sobering glimpse into the acute and enduring crisis that still exists for LGBTQ kids in school.

The survey’s reach has steadily grown: What was a limited sample of about 1,000 students aged 13 to 21 is now closer to about 17,000 participants. The current population sample is broad and representative, according to Kosciw, but there’s a critical caveat: Only the young people who feel comfortable discussing LGBTQ issues are taking the survey, which means thousands upon thousands of kids still aren’t taking part. “There may be people who are not sure, questioning, or identify as LGBTQ only to themselves—but still don’t feel comfortable connecting even to an anonymous survey,” he explains. “Those might be the most isolated people and perhaps the most in need of support.”

I sat down with Dr. Kosciw to look at how the experiences of LGBTQ students have changed over the last 20 years. We discussed the challenges that schools still face in supporting these students, the availability and benefits of school-based supports, and how educators at all levels can help.

Paige Tutt: What were some of the early findings about the experiences of LGBTQ students when the survey began two decades ago?

Joseph Kosciw: In 2001, the vast majority of LGBTQ students were hearing homophobic remarks in school, and high numbers were experiencing verbal and physical harassment, particularly around sexual orientation and gender expression.

Fewer students—although still a significant number—said they had supportive educators: an adult in their school who was supportive of LGBTQ students. At the same time, there were fewer Gender-Sexuality Alliances (GSAs).

The negative indicators of climate—bullying, harassment, name-calling—were high, and there weren’t a lot of resources out there for LGBTQ students.

Tutt: Back then, there was a general feeling in schools that anti-gay harassment wasn’t an issue, that name-calling was a normal part of adolescence, and phrases like “That’s so gay” didn’t hurt anyone. Have these attitudes shifted?

Kosciw: To this day, there’s still this common wisdom in the United States that “kids will be kids” and name-calling is “just part of growing up.”

But in recent years, we’ve begun to see people paying more attention to the effects of bullying and harassment.

Some will say, “Well, they’re LGBTQ students; they’re going to say that’s why they’re bullied.” So we did a survey—From Teasing to Torment: School Climate in America—with a national sample of secondary school teachers and students to get a sense of what they saw going on in school. We asked, who has the hardest time in school? Who is most at-risk in your school for bullying and harassment? Who faces the most negative climate?

Teachers and students both said: It’s the LGBTQ students. There is now an increased consciousness about the issue; that’s one thing that has changed in the last 20 years.

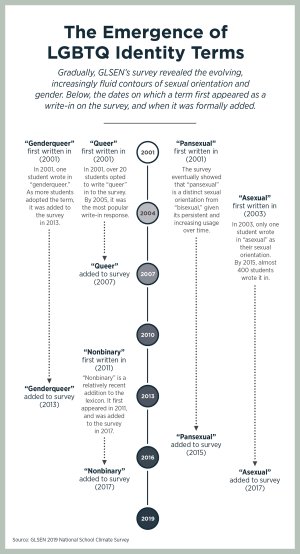

Tutt: You’ve tracked the emergence of terms like queer and asexual as they gradually moved into the mainstream, sometimes 10 to 15 years after they first appeared. How have the ways adolescents identify themselves regarding sexual orientation and gender identity changed in the last 20 years?

Kosciw: More and more adolescents are feeling like they don’t want to use terms. They don’t want to be boxed in; they don’t want to use gendered pronouns. Students are describing themselves, their sexual orientations, and their gender identities in an expansive way. As a result, that expands the population of youth that we’re talking about.

That’s why it’s important to look at things like differences in sexual orientation and gender identity. For example, we’ve historically found that schools can be unsafe for the majority of LGBTQ students—but it’s worse for trans and nonbinary students.

It’s important for us to understand the many ways that youth identify so that we can continue to understand how they’re seeing themselves and do the work necessary to include them. As the terms evolve, the need for professional development among educators must evolve too.

We know that professional development for school professionals on not just bullying and harassment in general, but on LGBTQ student issues more specifically, makes a difference to this population.

Tutt: As more cisgender straight people hear terms like nonbinary, there’s often a reaction like, “These terms just came out of nowhere within the last few years.” In reality, a lot of terms have been used for some time now, and they’re constantly changing and evolving. What challenges do you see in how schools meet the changing needs of LGBTQ students?

Kosciw: Our whole culture is gendered, and schools are very gendered: public spaces with boys’ bathrooms, girls’ bathrooms, locker rooms. A good friend and colleague of mine from a school district said, “The teachers are great when a student is a trans girl or a trans boy. They know what to do.” Because it’s still in that gender binary framework. “Oh, a trans girl, well, you should use girls’ facilities because you’re a girl,” right? But they don’t know what to do with nonbinary students because schools aren’t set up to have people who exist outside of that binary.

Transgender youth who identify as male or female want access to the facilities that are aligned with their gender. Youth who identify as transgender or nonbinary want all-gender spaces. I think that’s something that we might be seeing differently as these terms evolve—changes in architecture and the building of new schools, creating more expansive, inclusive facilities that aren’t as gendered.

Tutt: Your research also looks at the experiences of LGBTQ youth of color and how they differ from the experiences of their White LGBTQ peers—why is this important?

Kosciw: It’s really important to point out that LGBTQ youth are not a monolith and that their experiences really do vary based on a lot of different things.

We did a series of reports last year exploring the experiences of AAPI, Black, Latinx, and Native and Indigenous LGBTQ youth.

We found that 40 percent of LGBTQ youth of color experience victimization in school because of their sexual orientation and their race/ethnicity. And that’s across all racial/ethnic groups. That’s important because we often think, well, you’re a student of color or you’re an LGBTQ student, right? We box people in to make sense of them.

It’s important to look at those intersections because students who report high levels of both types of victimization have the worst outcomes. If you’re experiencing high levels of racist victimization and anti-LGBTQ victimization, you are worse off and need the most support.

Tutt: That brings me to how teachers can help. Becoming isolated, grades dropping, frequent absences—these are all indicators that a student is struggling—whether they identify as LGBTQ or not. But beyond these red flags, what should teachers be focusing on?

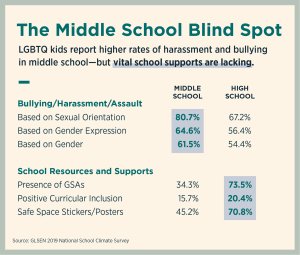

Kosciw: It’s important to look for those signs, but preventative measures are even more important, and they need to happen early. We do find that youth in middle schools have a far worse time than in high schools. It’s important to think about all of these years, not just high school.

You can interrupt negative events when they happen in school—homophobic remarks, transphobic remarks, racist remarks—because when those things are not interrupted, that can be interpreted as the teachers “giving permission.”

But it’s also about creating an environment that embraces difference and diversity—and teaching an inclusive curriculum so kids connect to their learning. The “windows and mirrors” idea of being able to see yourself reflected, but then also seeing the experiences of other people and how you fit into that larger world of diversity inside your school.

Tutt: Are there other ways educators can support LGBTQ students?

Kosciw: Put up a safe space sticker. It’s something that indicates that a teacher is there as a support to LGBTQ students. Sometimes it’s hard for students to know who to talk to and who would be comfortable talking to them, especially if they’re coming out or questioning.

Also, being a Gender-Sexuality Alliance advisor or helping to start a GSA in your school is another great way to demonstrate visibility.

Our research has shown that there are four major ways that schools can cultivate a safe and supportive environment: curriculum inclusion, having a number of teachers who are supportive, having a GSA, and LGBTQ-affirming school policies that prevent negative behaviors like bullying, harassment, and assault. All of those things really do make a huge difference in not just the well-being of students, but their psychological attachment to school: their performance in school, wanting to continue their education, and their educational aspirations.

Tutt: What continues to worry you?

Kosciw: The insidious ways in which anti-LGBTQ and racist attitudes can still manifest themselves in schools and school buildings. That’s where discrimination comes in: “Yes, you have a right to feel safe in school. You shouldn’t be called names. You shouldn’t be beat up. However, we are not going to let you be who you are, with full access to school life. You may not bring a date of the same gender to the prom. You may not use the locker room or bathroom that aligns with your gender identity.”

It’s not just about students feeling like they can go to school without getting beat up. Do they have full access to school life? Beyond safety, do they have the same access to education in the school building that other students do? There’s really more to school than just feeling like, “OK, I can go and not feel like my life is threatened by entering my school building.”

Tutt: And finally, Dr. Kosciw, what makes you hopeful?

Kosciw: I think we see that these preventative measures make a difference—and I’m hopeful that we’ll continue to see change in those areas. I’m also hopeful because people are talking more in schools about the diversity and intersections of identity, really trying to understand the needs of LGBTQ youth of color versus White youth. They’re looking at the racial composition of the school, assessing the needs of the students and where they are.

And we see an increase in Gender-Sexuality Alliances. Even if a student doesn't go, they know they can. It’s a safe space if they need it.

These changes that we’ve seen over time bring me joy, they give me hope—these things make a difference. But there’s a lot more work to do.